In 1918, Mardi Gras was cancelled in New Orleans on account of the World War. It was cancelled again a year later, in 1919. A series of events during those years conspired to cancel jazz as well.

Storyville, the legal prostitution district that had done much to incubate the new music in its honky tonks and sporting clubs, was closed at the request of the Army and the Navy in 1917. The following year, the New Orleans Times-Picayune published a floridly racist editorial describing jazz as a moral abomination, calling the music an “atrocity . . . its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great.” The editors called on the city to suppress the new music in its cradle. The Great Influenza descended on New Orleans later that year, all but forcing the remaining clubs and music halls to shut down. But most of the musicians who had created the new form had left by then anyway, finding more receptive audiences in Chicago, and later in New York and California.

Still the music grew to outlast its various existential threats, thanks to the genius and persistence of a handful of musicians who remained in New Orleans. Their music is one of the subjects of King Zeno, and it can be heard below.

Included in this playlist are some of the very few recordings from this period. Though not entirely accurate, the Original Dixieland ‘Jass’ Band, a group of white jazz musicians from New Orleans living in Chicago, are widely credited with producing the first jazz recording in 1917. But the sound of this transitional moment—when jass became jazz, and the music crossed over from a threat to society to the basis for a new society—can be reconstructed through later recordings. Some of these were produced by the original musicians, after jazz had brought them fame and respect; others were made in their memory by disciples.

They all swing.

TRACKS:

1. Original Dixieland Jass Band: “Livery Stable Blues”

2. King Oliver: “Dippermouth Blues” (second cornet, Louis Armstrong)

“So much for New Orleans. For all the bluster about its sophistication and grandeur—‘the American Paris,’ ‘the Metropolis of the South,’ and poised, upon completion of the Industrial Canal, to be a ‘city of the future’—there was no escaping the fact that it was run by waterbrained bureaucrats and unreconstructed bigots who couldn’t make it in St. Louis or Cincinnati, let alone New York City. What did it say that King Oliver had to supplement his income by working as a butler in the Garden District, before the shame forced him to flee for Chicago?”

3. Kid Ory and his Creole Orchestra: “Muskrat Ramble”

“Isadore had always understood music as a conversation with the Dark Unknown—the dimension of the world that was hidden to the world, that bubbled beneath the surface, or above the surface, or in parallel to the surface, what Miss Daisy might call the ‘spirit realm,’ or what he’d once heard Kid Ory describe, in a set at Economy Hall, as ‘the dominion of the imperceivable.’”

4. Louis Armstrong: “Cornet Chop Suey” (Armstrong’s first recording under his name)

“Louis ‘Dippermouth’ Armstrong was playing on Fate Marable’s steamer and hadn’t been seen in months . . . ”

5. Jelly Roll Morton: “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say” (“Funky Butt”)

“She got the life-historical importance of this night. She got the Funky Butt.”

6. Zutty Singleton: “Moppin’ & Boppin”

“Big Head Gaspard’s hands chased each other across the length of the piano, Little Head bent halfway over as if to keep his saxophone from blowing off the roof, and Zutty Singleton himself—Zutty, the hardest-hitting drummer in New Orleans—hit the tom with such force that the stand began to hop away from the rest of the set.”

7. Preservation Hall Jazz Band: “Tiger Rag”

“The Fiss Fass Jass Orchestra crested into a full giddy frenzy, teasing apart the Tiger Rag like an old sweater until it unraveled into something unrecognizable and frightening.”

8. Punch Miller: “Bucket’s Got a Hole In It: A Demonstration of Buddie Petit’s Style”

9. King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: “Snake Rag”

10. Johnny Dodds: “Wild Man Blues”

11. Lee Collins: “Royal Garden Blues”

“He thought of the other musicians at the Cosmopolitan tonight: Buddie, Honoré, Dodds, Collins. They had seen what he did and they had seen the response. They knew Isadore would never leave New Orleans; undoubtedly they would take his tricks on the road. Maybe they would give him credit or maybe they would pick from his style what they liked and pass it off as their own. The idea would have bothered him only days earlier but now he accepted it in a spirit neither happy nor sad. The song was his only for a little while. Then it was everyone’s. If it were a good song—a real, honest song—and it had a swing, it would be sung forever.”

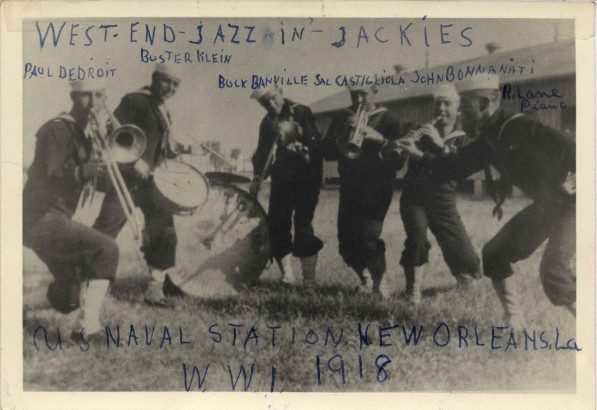

West End Jazzin' Jackies at the U.S. Naval Station, New Orleans, 1918; Paul Dedroit (trombone), Buster Klein (drums), Buck Banville (violin), Sal Castigliola (trumpet), John Bonnanati (clarinet), R. Lane (piano)

West End Jazzin' Jackies at the U.S. Naval Station, New Orleans, 1918; Paul Dedroit (trombone), Buster Klein (drums), Buck Banville (violin), Sal Castigliola (trumpet), John Bonnanati (clarinet), R. Lane (piano)