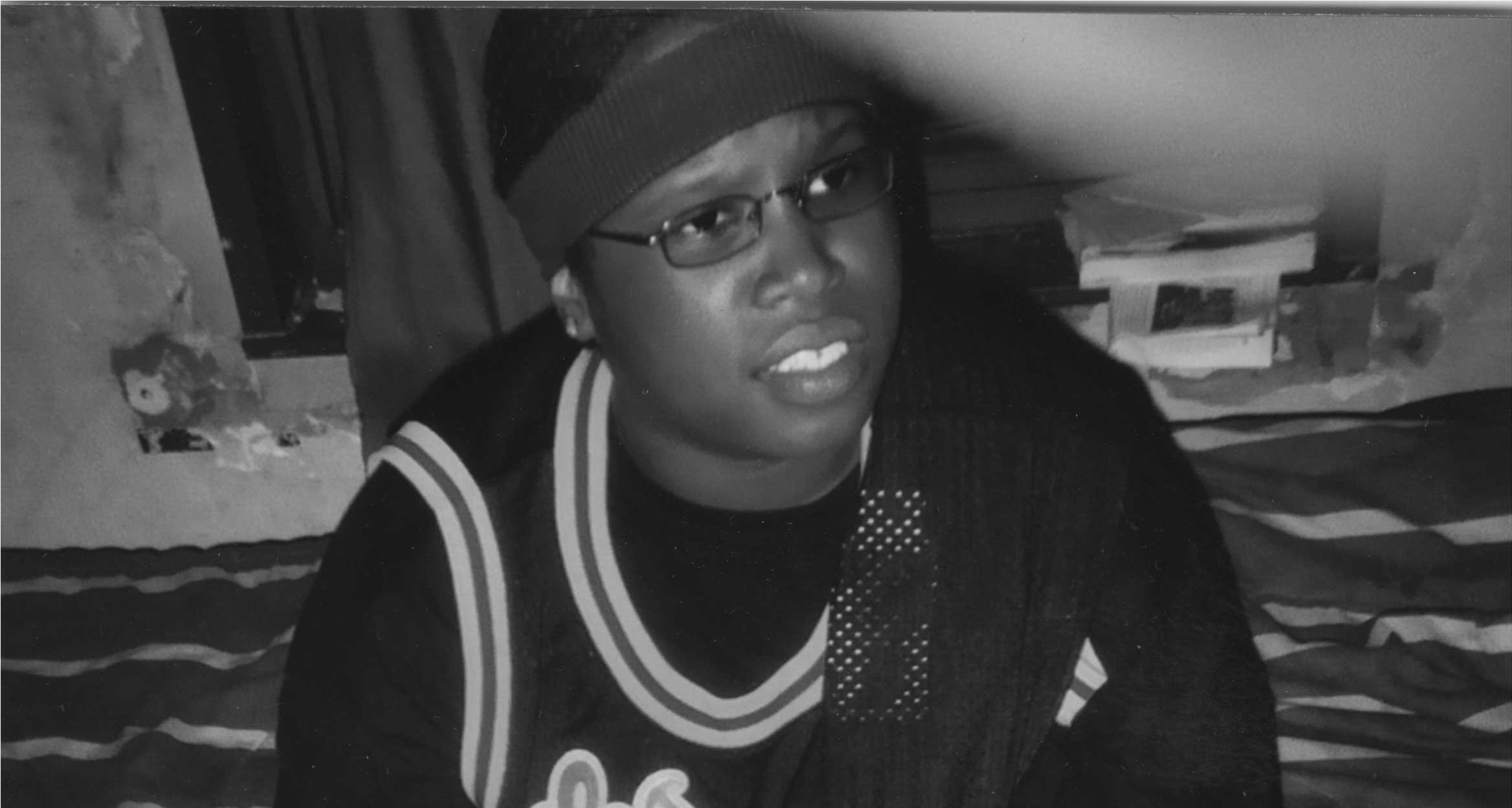

Growing up, Roya Marsh was considered “tomboy passing." With an affinity for baggy clothes, cornrows, and bandanas, she came of age in an era when the wide spectrum of gender and sexuality was rarely acknowledged or discussed. She knew she was “different,” her family knew she was “different,” but anything outside of the heteronorm was either disregarded or disparaged.

In her stunning debut, written in protest to an absence of representation, Marsh recalls her early life and the attendant...

The essay below is excerpted from dayliGht, the debut collection of poems by Roya Marsh

REPRESENTATION MATTERS. I was eight years old the first time I saw a representation of someone like me. It was 1996, when Queen Latifah made her big-screen debut as Cleopatra “Cleo” Sims in F. Gary Gray’s Set It Off. It meant everything to me to see a Black woman living her life openly gay; openly masc presenting; with cornrows, baggy jeans, plaid shirts, and big breasts. I was twenty-eight years old when Lena Waithe became the first African American woman to take home an Emmy award for her work on Aziz Ansari’s Master of None. The episode for which she won the award chronicles the coming-out story of Waithe’s character, Denise. These are representations that have buoyed and emboldened me.

“It meant everything to me to see a Black woman living her life openly gay; openly masc presenting; with cornrows, baggy jeans, plaid shirts, and big breasts.”

Children who are sexually assaulted are reborn into fire. There’s always a trail of smoke. There’s always a pile of ash. Some folks believe these assaults might sway our sexuality. Sometimes, this is true. But it’s not always the case. At least, it wasn’t for me. Both trauma and the attendant coping mechanisms we devise to live with trauma manifest in countless ways—it all depends on the host upon which our traumas feed.

I knew who I was and who I was going to be well before I was assaulted. I was eight years old when I knew I was going to love women romantically. Even at that age I knew what desire looked like. The youngest of eight children, I was hypersexualized by proximity. Sex was everywhere. Yet, my exposure to sex was limited to heteronormative behaviors and depictions.

I knew I was “different.” My family knew I was “different.” But homosexuality wasn’t something that was prevalent, much less discussed, in my family. Anything outside the heteronorm was passed off as “funny.” My sexuality was either completely disregarded or couched in homophobic epithets. From the moment I was able to dress myself, I wore windbreakers and superhero T-shirts. Dresses, barrettes, and the like were never my thing, but I wasn’t in charge of my hair just yet. In overalls, I was “tomboy” passing.

“From the moment I was able to dress myself, I wore windbreakers and superhero T-shirts. Dresses, barrettes, and the like were never my thing . . . In overalls, I was 'tomboy' passing.”

Experiencing an assault in my childhood made me vulnerable to assault in my teenage years. Later, seeking support, I found brick walls instead. To this day, I’m met with ignorance when I raise the subject with those closest to me. Some folks just can’t fathom any hetero-predator wanting a girl like me. Some folks just can’t fathom a woman like me having sex appeal to a man eager to conquer. Most days my femininity is catcalled into existence. I’m considered just woman enough—enough to fuck into a condition the world will accept. I know representation isn’t a cure, but it’s a start. I fear violence against my community will continue to go unabated unless we continue to tell our stories and fight for a wider understanding of the full spectrum of sexuality and gender. When I see Cleo, I see myself—even if I also see a level of toxic masculinity and an objectification of women in her character, that I struggle against. In Cleo, I see wit. I see strength. I see pride (to a fault). And I see a woman with a drive to become utterly unfuckwithable. When I see Denise, I see myself. I see a woman living her best lesbian life; dealing with the ebb and flow of others’ perceptions.

SINCE THE RISE OF THE #MeToo movement, I have longed (perhaps, selfishly enough) to see women who look like me come forward. Of course, that’s not to say that I want to see us as victims. Rather, I want the world to know that there isn’t only one type of victim. I’m calling us to the front because I know we exist—women, like me, trapped in yet another closet. I don’t see our stories represented often enough. I want the Google image results for search terms like “strong Black woman” and “bad bitch” to look like us, too—the Masculine of Center (MoC) woman, the butch, the colored dyke, the survivor who struggles with forgiveness. I am forever indebted to those writers and artists who’ve showcased these characters and narratives—to Audre Lorde, and Barbara Smith, and Anita Cornwell, and Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and June Jordan, and countless others. It is my hope to add an ember to the flames they’ve lit. We often forget the wonders of fire. There may be smoke at the start and ash at the end, but always in its wake lies evidence of the work done to light the way.

Vist Literary Hub to read “in broad dayliGht black girls look ghost,” an excerpt from dayliGht, Roya Marsh’s debut collection of poems.