Dear Margaret,

Martin is dead. It was an accident on the docks. I paid for a good burial and a stone in the cemetery, where wild roses grow at his feet.

×

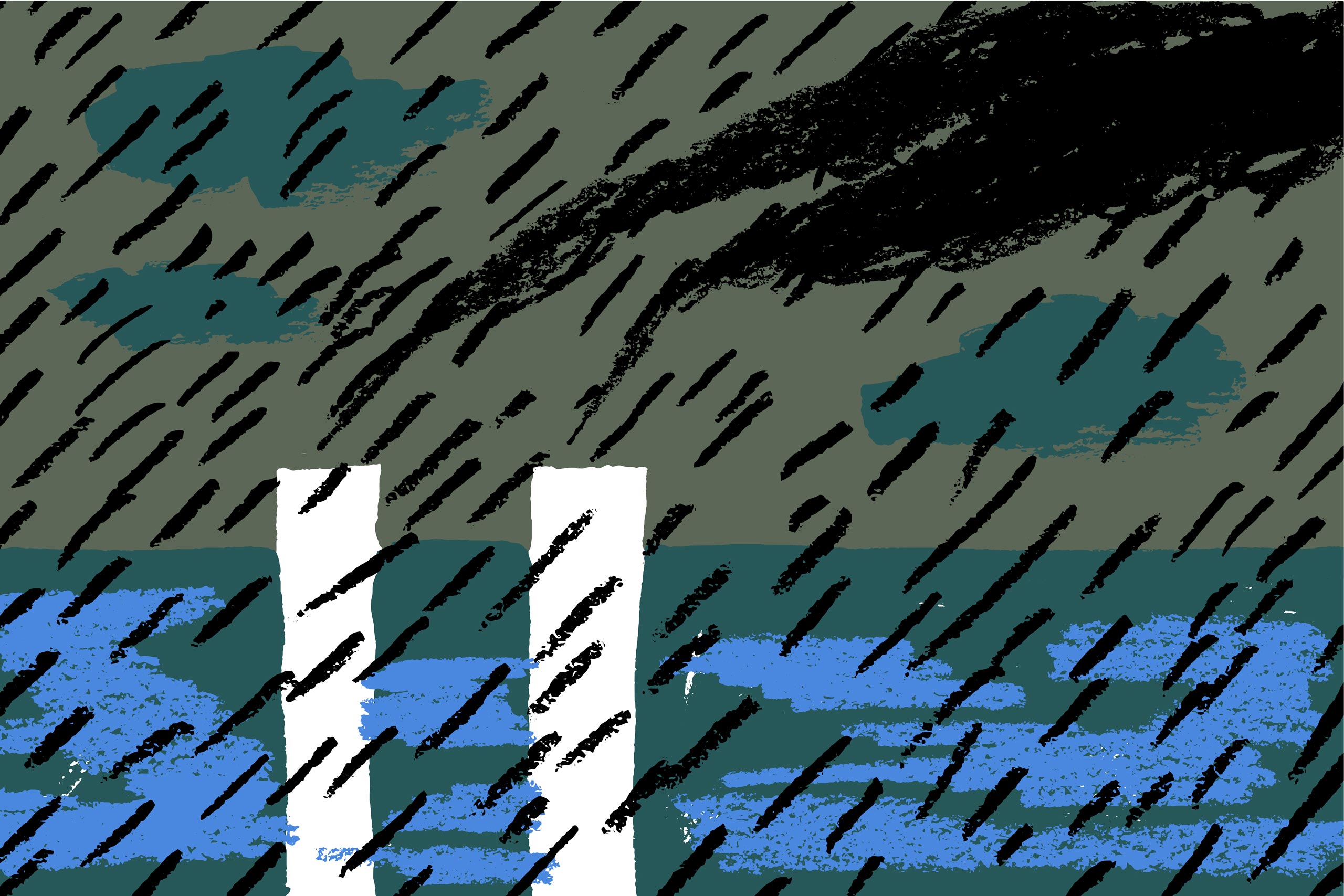

Fifth in line, low on the shuddering gangway, Tom McManus heaves a sack to the man above him. When his hands are empty he catches his breath. The air is bitter with charcoal — the whole world scorched with hellfire since he woke that morning in the candlelit disease of three o’clock, gin sick, feverish, wicked sparks flaring in his kneecap. He had dreamed of his brother.

“One, two!”

Another sack. Tom leans hard on his right leg and takes the load with both hands. The dirt-streaked burlap holds one hundredweight of barley. He clenches his gut and thighs. Tosses the bag up. One, two; grip, heave. Breathe.

Then, lights flicker in the distance. He squints past the tarred mooring ropes, past the curving plane of Lauralee’s hull. Two red dots hover over the river. They narrow, grow nearer. His fingers claw against burlap as his nightmare creeps from the shadows and he sees Martin’s face behind the unblinking red glare — Martin’s eyes were full of blood Martin’s eyes were full of rage to be cut down in the bloom of health to be cut down in the bloom of summer when this foreign place smells of pitch and opium to be cut down howling brother I will return —

Tom’s heart punches against his breastbone. He swings the bag up to Lindstrom and sketches a cross from brow to chest, mouthing his brother’s name. But the lights widen, separate. Take shape as the burning chimneys of an approaching steamboat.

“Come on, lads!” The foreman paces the dock, his bulk draped in streaming oilcloth. The next steamer is ready to take its place at the berth, so it’s quick, boys, quickly now! Then the foreman’s shouts are drowned by a triple blast of the steamboat’s horn.

A wake rolls in from the waiting boat. The gangway shifts sideways. Tom, still dazed by his brother’s face, forgets the softness of his left knee and braces that leg. Bone grinds on bone. He hinges forward, gasping.

“Too busy to be tired,” Lindstrom says, vowels weighted down by his mother tongue.

Tom wheezes, teeth tight, fists tight. His kneecap is a hollow coal, crawling with fire and ready to crumble.

That god damned fight. He should have walked away. It was not his trouble. But the gin sloshing in his stomach made him feel broader, angrier. And the cornered man had sounded so much like Martin. Looked so much like him, in the midnight alley. So Tom threw himself at the two attackers. And for what? Not a word of thanks, only the swing of that billy club against his knee. Brass-tipped black wood smashing down. The sound had been the worst thing — the crunching.

Rain hisses into the river, into Tom’s narrowed eyes. His right leg cramps with use. Lindstrom tells him to turn up, turn up! But he can’t swivel on his knee with each bag. He locks his jaw against the cry forming in his throat.

“I am doing all your work,” Lindstrom tells him, as Tom wipes his nose.

“All right, Lindy.” He directs his glare for Lindstrom at the river, where gulls flap and squabble.

More bags. The gangway shudders with each catch and heave. Steam rises from the men’s shoulders, their open mouths. Tom counts to ten and back again, until grey light seeps into the sky. Sideways rain kicks into his gritted teeth. The gulls below are screaming.

“Belay!” At last.

The men in the hold crowd onto the steamer’s deck and jostle past Tom. He leans into the side rope, his ears and neck burning. His breakfast of coffee and hash is crawling up his throat faster than he’s hobbling up the gangway. Lauralee’s captain blares the horn. He is alone on the gangway. He limps up plank, by plank, by plank.

On the dock men swarm around him, whipping loose the tie lines. Lauralee swings free. Her sidewheel beats the water into foul yellow foam that spatters Tom’s open mouth, his heaving shoulders.

“I’ve got no use for a man that can’t walk,” the foreman tells him.

“Sir —”

“Be back in line in two minutes or get lost.”

“Come on, come on.” Lindstrom tugs Tom away, leading him through the sheets of rain to a crate near the pier’s edge.

“Is that from your fight last night?” His chin dips toward Tom’s knee. “You should not drink so much.”

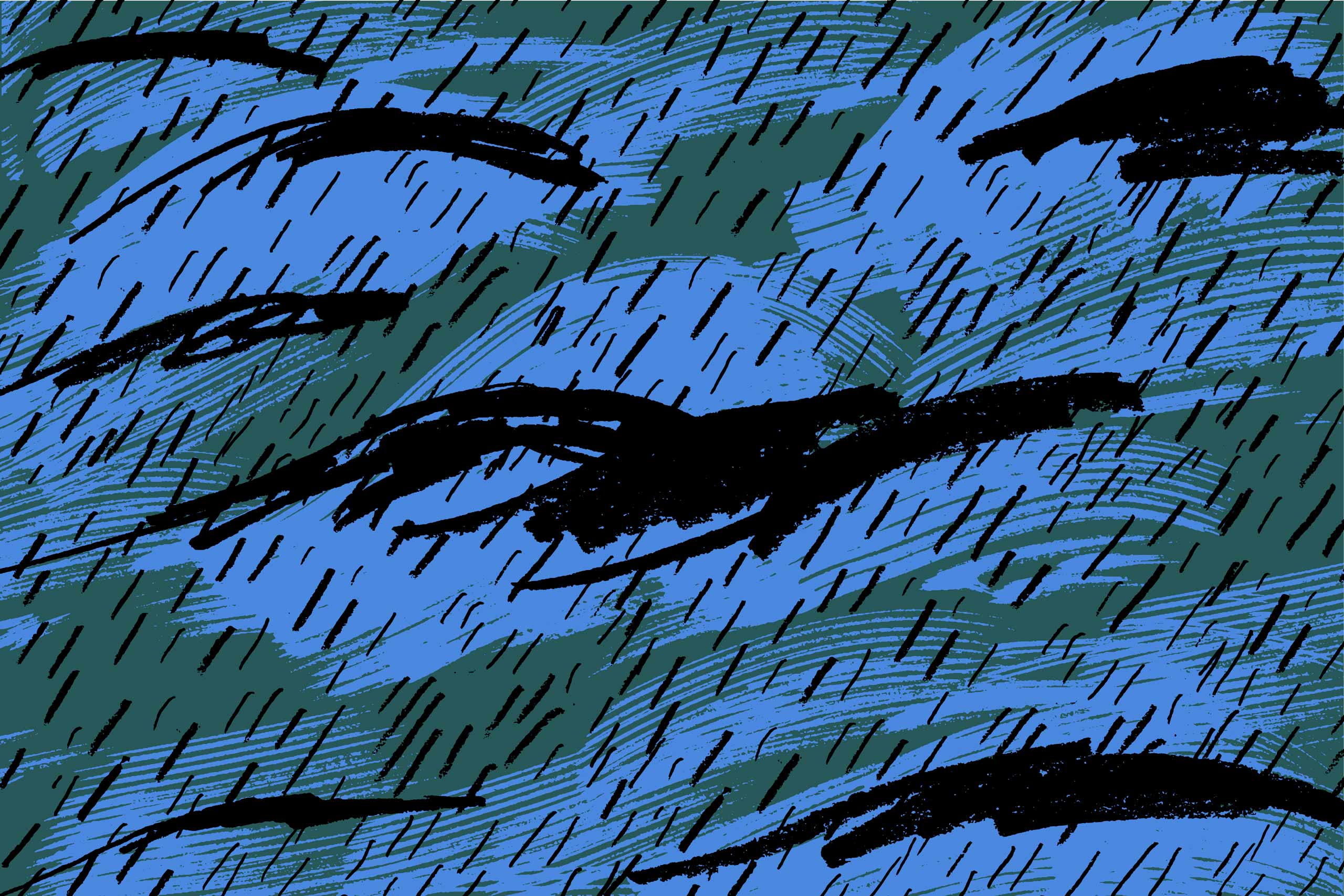

“Just give me a minute. Christ.” Tom bats Lindstrom’s hand away, staring past him at the river traffic. Gillnetters tack down from the Columbia. A drowsy whiskey scow noses along the shore. Northbound steamboats ride low in the stream, so stuffed with grain they leave a golden skin of wheat chaff on the river. There will be a string of good paydays on the docks with this harvest.

“God damn it,” Tom says.

Lindstrom offers his hand again. Tom shakes his head.

“Get back to the line,” he says.

The waiting boat ties in. The men assemble. They’re strong and quick, moving in a smooth accordance that puts Lindstrom fifth in the gangway body chain. No place for Tom among them now.

×

Dear Margaret,

Martin is dead. An unlucky brawl. You know how he loved to box, though your da warned him to keep off it. He died quick and that’s all I will tell you of it, to spare you grieving. I am bearing up all right though it’s the hardest loss I ever had and I wish you were here with me. He is laid to rest in a good plot. I could not afford a stone but I put your locket with your curl of hair in his breast pocket, to be with him always.

×

The boarding house, bed, a bumper of gin. Tom conjures these rewards as he turns on Second Street. Only a mile separates him from his lodgings. No distance at all. On a few late mornings he’d sprinted to work in less than eight minutes.

Now even a shambling pace squeezes air from his lungs. Cart clatter and workmen’s conversations muffle his uneven tread, but he is ashamed of his slumping shoulders, ashamed of his left boot’s drag over the sidewalk planks. Gutter runoff worms under his collar. The grinding in his knee travels up his spine to echo in his skull, which is still gin-dented and tender. Still stained with guilt.

Days of rain have soaked Portland into a gray-brown sludge of wood and mud. Yet vents of subterranean fire surface in the brickworks’ concrete furnaces, the gas lamps outside the shipping office, the taper burning behind broken glass in an alley-side apartment. Flicker, dim. The dark is waiting — on the train through midnight desert we collected drops of light and made them into comforts that one’s a candle on a dressing table where a lass takes down her hair that one’s a kitchen where they’re baking hot oat cakes can’t you smell them so sweet that one’s a pair of brothers just discovered gold their lantern’s lighting up their bounty like a hundred suns he said Tommy one day we might be so lucky —

His kneecap pops sideways. He drops against a wall, cursing, his weight on his good leg. If he sees that ginger bastard with the billy club he’ll have his fucking bollocks, he will, but even as Tom thinks this he knows he’s hearing Martin’s voice rather than his own.

His brother the bloody-knuckled. Martin, who taught him to be tough though they were both undersized, how to swing like a hardened auld brawler though Tom had not yet hit twenty. Martin, older, golden, always on coming out on top until the July night he toppled over, roaring, onto the straw-dusted saloon floor, the pint in his hand smashing into a firework of foam and glass.

Margaret’s first letter arrived two days after, when Tom felt bruised all over by his brother’s death. To read it was to take another beating. Body blow: His cousin’s careful printing, the soft curve of her signature. Uppercut: Her recounting of Sunday dinner—buttery food, toasts to Tom and his brother, the life he’d left behind. Haymaker: Inside the letter was a locket and a folded paper with one line: “I’ll wait for you, sweetheart.” It was addressed to Martin.

Tom keeps Margaret’s locket in his vest, wrapped in a bit of linsey-woolsey to guard its filigree. He dips a hand into the wet wool at his middle. Finds the trinket. Its ridges tick across his thumb through the faded cloth. In five seconds he will shove off the wall and start walking. Four. Three.

“McManus.” His name, rough with a Lochaber burr, hooks Tom’s attention.

A man waits on the sidewalk. Black hair curls under the brim of his hat. He wears a fine-cut wool coat. Pleated trousers nip to points over leather brogues. A gentleman. Tom knows him, though they have not spoken or been introduced.

“Can’t help you this time, pal,” he says. “Your friends from last night made a mash of my knee.”

“A shame,” the man says. His plaid scarf is worked in sharp blues, like the sky after a rainstorm, when all the colors hurt the eyes.

“Looks like you survived,” Tom says, but his sneer falters when the man steps forward. There’s swelling under his left eye, a bruise along his clean-shaven jawbone.

“Take a walk with me, McManus,” the man says.

“I’m a bit slow the now.”

“My offices are just down Third. Warm up with a cup of coffee.”

Tom does not want a cup of coffee. He wants his cot, and the quiet of the half-pint of gin tucked under his bed.

“I’ll be going home,” he says.

“Harrison’s cut you from his crew.”

Tom stumbles as he walks away. Pain twists his words into a low growl.

“And how the fuck do you know that?”

“The docks are my business.”

The man comes closer. He is an inch or two taller than Tom, with narrow shoulders. Martin’s build. The night before, in a cropped jacket, he had looked younger — twenty-one or -two. Martin’s age. Now, at arm’s length in the rain-dimmed daylight, he has deeply lined eyes, blue instead of Martin’s brown. His hair sparks silver at the temples. Tom wonders that he saw any resemblance at all.

“You’re missing the grain run,” the man says. “Three, four weeks of padding your pockets for winter. What will you do, with your knee?”

“I’ll sort something out.” But Tom thinks of snow. Does it snow here like it did back home? Waking to the taste of iron, brittle air, the cries of seabirds muffled in thick white drifting. He thinks of the old tomato tin where he keeps his money, all those flimsy foreign coins. Hotcakes and coffee and bacon rashers from the boardinghouse, two cents.

“Maybe I can help,” the man says.

“So that’s how it is.” Tom shoves his fists deep in his pockets. He stands tall though the pressure on his knee shortens his breath. “The rich man looking out for the poor, aye?”

“If you’re naught but a beggar you can have everything in my billfold,” the man tells him. “But I think you’re worth more, Tommy.”

How does this man know his name? Tom searches his face for the edge of something familiar — the reflection of a shipmate from the crossing to New York, or a businessman encountered on a dusty interior train. No memories surface.

“I work for my money,” Tom says.

“As a man should.”

He is tired by this dance. Tired by the thought of the long walk home. He’ll take that coffee now, just to have the chair that goes with it.

“All right,” he says. “What work have you got?”

×

Dear Margaret,

Martin and I are well. We’ve found work with a crew on the waterfront. Since we left home I’ve grown a notch taller than Martin, which doesn’t please him though it pleases me. He can still lift heavier loads, but with each day on the crew I get closer to besting him. I bet him a pint of bitters I could take him at arm wrestling by Fair Holiday so you can expect another letter then all about my victory and the blood on the glass the red glass pieces the —

×

The gentleman’s name is Nathaniel Wheeler. He installs Tom as crew supervisor on Davis Street pier, where he works with a steady gang of men: two Swedes, two Scots, an Irishman and a massive American boy who talks like he’s got a mouthful of cotton. The boy says he’s from a logging town in the Idaho Territory. Tom doesn’t recall passing through that place. Perhaps all its men are giants — growing up among colossal trees so their arms, too, are thick and knotty, their shoulders broad.

Wheeler’s boats load at all hours. Nighttime runs allow Tom to sleep past sunrise. On clear mornings he sits atop the river pylons with a breakfast of rye bread and cheese. Pine spices the breeze. He tracks waterfowl as they feed and dive and glide. Drakes, with their drab little mates, he knows from home. Green-winged teals, Margaret’s favorite eating bird, which Tom would present to her in dripping bouquets while Martin laughed at his flushed cheeks. Goldeneyes. Most others he cannot name.

During his first week on the dock Tom hangs back while his crew loads. He is shy about exposing the weakness in his knee. It heals slowly, incorrectly, so even when the worst pain fades a broken chip works against the bone, like a jagged tooth. He wakes from dreams of goblins gnawing on his leg, two red eyes in the dark, a weight on his chest. Lindstrom tells him he talks in his sleep.

But their lives are shifting apart. They share the same room at the boarding house, the same tilting table and chairs. Lindstrom works on Harrison’s crew from four a.m. to after noon. Some days they meet only once, when Tom’s coming home from a night job and Lindstrom is just getting up, a single candle on the dresser, the razor’s scrape over his chin. They share no breakfast or coffee, no evening games of cards under the smoking lantern. The room’s smell changes: blue mold veined on the ceiling, a stranger’s filthy shirts.

Tom receives his first payment in Wheeler’s offices: ten dollars and a switchblade. He doesn’t want the knife — he puts his hands in his pockets when Wheeler holds it up.

“Don’t like a blade, Tommy?”

“Never had one.”

“Now you do. You don’t look a shrinking violet, but some of the waterfront crimps get bold after midnight.”

Wheeler’s bruises from the back-alley fight have faded to green smudges on his cheek and jaw. He tips up that side of his face. Raises an eyebrow.

“Bloody bold,” he says.

Tom steps forward. He takes the knife — blade ablaze in the barroom lights — and as the notched haft rasps against his palm — hot blood on his hands, wet sparkle of glass — his heart slams so loud he nearly misses Wheeler’s next words.

“You’re doing well,” Wheeler tells him. “Don’t be mistaking why I picked you out as crew lead. If I were merely grateful you’d come to my aid, I’d have given you some coins and said godspeed. But you worked hard for Harrison. I trust you’ll work as hard for me.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good.”

Tom inspects the knife. He’s never seen one of this design, with a split handle that swings closed to conceal the blade. He runs the tip of one nail over the hidden sharpness. Tries to shake the handle open again, covertly, so Wheeler won’t see his confusion.

“You daft bastard.”

To Tom’s surprise, Wheeler laughs and comes around his heavy oak desk to take the knife.

“Like this,” the older man says. He flicks his wrist to unleash the blade. “Ah?”

Tom tries out the motion. The steel edge snaps out and he startles. This time he laughs along with Wheeler.

“Go spend your money,” Wheeler says. “Some nice girls at Erickson’s down the way. Some not so nice ones, too, I hear.”

Tom’s ears flare hot. He’s only thought of one girl, lately — a girl who is oceans away, fading into paper and ink and a lock of black hair. But even as he blushes he smiles, because it is pleasant to see Wheeler in a jovial mood, to be spoken to like a familiar. Like a brother.

After another week of work on Davis Street pier, Tom worries his muscles are going soft. Despite his knee, he joins the men: stages cargo for them to shift, limps among them until his clothes, too, are streaked with dirt and sweat. If they pity him they don’t show it, so Tom lets himself be friendlier. Lets the men be friendly to him. As he settles in among his crew he learns who is the hardest worker, who is the prankster, what each man needs to hear to give his best.

Wheeler sometimes visits the pier. He carries a polished walking stick. A new gold ring shines on his finger.

“How’s things, Tommy?” he asks, and each time Tom is proud this successful gent picked him out as a reliable man. Tom McManus, crew lead at nineteen. Tom McManus, salaried at ten dollars a week, plus the occasional gin in Wheeler’s offices. Tom McManus, coming out on top.

×

Dear Margaret,

I love you. I beg your forgiveness. I cannot unsee his eyes. Red and terrible. Whole spots of that night are burned from my mind but not the truth of it and I cannot unsee his eyes. Red in the barroom lanterns. Red teeth. Red pieces of glass. O Cain! O demons! This is madness.

×

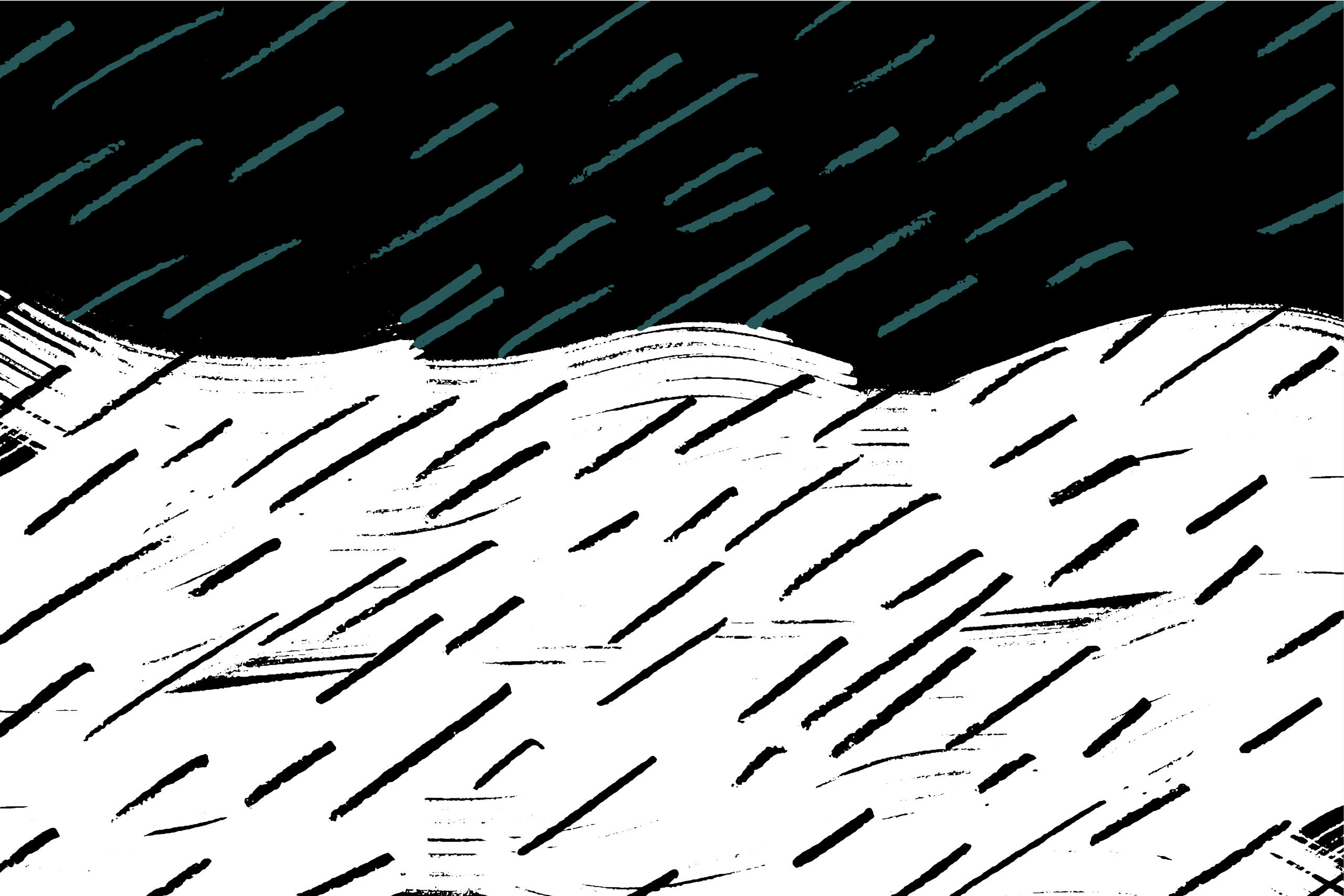

A night job. Just past one o’clock. Tom paces the halfway mark of the pier, where its pilings strike out into deeper water. Winter in the air outlines every breath. The quarter moon rises over a warehouse rooftop, over the shouts and carousing from the sailor’s bars on Front Street. There is no sign of his crew. Tom lopes back and forth, back and forth, forcing himself not to limp. He’s getting better at hiding his weak knee, and other things.

Movement on the corner. It’s not McIvor or Lewis or the massive Daniels — it’s the boss himself. Wheeler’s gold ring glints in the glow of his cigarette. His boots tap a measured pulse on the planks. His shoulders are held tight, his hat brim pulled low. He wears the bright blue scarf wrapped up almost to his unsmiling mouth.

“No other lads tonight?” Tom asks.

Wheeler shakes his head, flicks his cigarette into the water. Tom is pleased the boss would trust him alone with something important. He waits for instruction. Cold twists into the seams of his trousers.

“A barge will tie up here in five minutes,” Wheeler says. “Just after a cart. There’s no inbound cargo. Load the barge — then you’re free.”

“Yes, sir.”

Tom watches him stride away. Soon there’s only echoed singing from the saloons, bass voices slurring under the higher notes of girls. Yellow-haired American girls, Tom thinks. In green dresses.

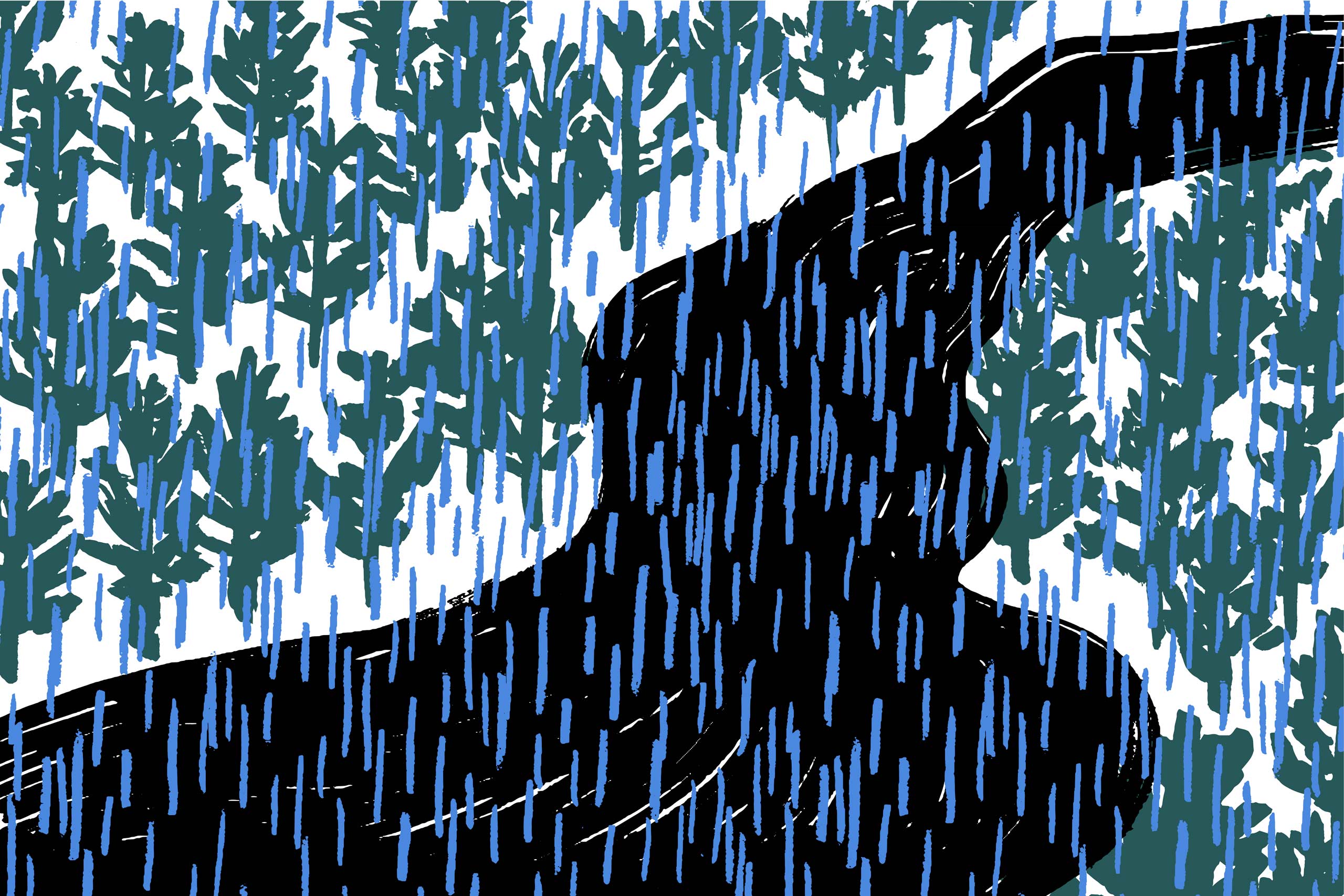

Starlight picks out frost on the plankboards at his feet. The moon skitters over the river. Tom rubs his hands together, and is blowing heat into the cup of his fingers when metallic hoofbeats shake the dock. A horse and cart. On high, under cloak and hat and muffler, the driver is a lump of darkness.

“All right, pal,” Tom calls.

The driver shifts but does not answer.

Tom approaches the cart. The horse is a tall animal with rum-barrel ribs. Steam rises off its glistening flanks. It smells of sweet hay, as does the canvas sheet tied over the cart bed. Tom picks at the rope knots with cold-stiffened hands. When the horse chuffs he looks up from his work. Beyond the animal’s head, at the end of the dock, a dark lantern floats above the river. The barge has arrived.

Hooking his fingers under the canvas, Tom snaps it back to reveal a jumble of sacks. He prods the nearest bag. The contents are dense, spongy. Not metal. Not cloth.

Tom does not want to clamber in and out of the cart on his unsteady knee. But the driver has shown no signs of stirring from his perch, and the swaying lantern is the only movement on the barge.

He plants his right foot on the baseboard. The long step into the bed sets off clicking pain in his kneecap. Braced for a heavy load, he bends his right leg and grabs two corners of the closest sack. When he heaves it over the side the impact shakes the cart.

Another bag. It thumps against the planks. Tom regrets the noise, but what else is he to do? The pride he felt earlier is spoiling into resentment. Wheeler knows his knee still gives him trouble, yet summoned him to toss around these sacks, which are close on fifteen stone and unpredictably hard in places.

It is not until he grapples the third bag up to his thighs that he recognizes its contents. Tom clutches the burden, back tight, biceps straining. The breath leaves him in a wheeze.

An elbow. There. Pressed into the crease of his hip. A long bone, hard against his leg. Round heaviness distorting one end of the bag. A head.

It cannot be long dead. There is no smell. The burlap is dry, with a supple give in places that speaks of just-cooled flesh — when I fell beside him Martin was still warm Martin was still breathing Martin was still Martin but how quickly that life faded how quickly he went heavy his limbs dense and drooping like lumps of dough I choked on my horror I choked on my silence choked because I’d seen his rival slip out a knife and had not cried warning had not cried stop had not said a bloody word O my brother —

Snap!

He flinches. The driver strikes his seat with the horse whip, again, and his message is clear: Get on with it. Tom swings the bag in his arms onto the dock.

He can walk away. He has not done wrong yet, at least not wrong enough. He moved some bags from cart to dock. There they lay still. But now he knows what he is handling. It is the next half of his task — lugging the bodies to the waiting barge, in which they’ll slip away upriver and disappear — that will damn him.

Damn him! Tom gives a strangled laugh. He has walked among jets of hellfire these six months past. And the burlap-shrouded dead are not his own. They cannot be rescued. They cannot be warned.

A long shape gleams between the last two bags. Tom leans forward. His fingers close around smooth wood, and the night changes color once again. He holds an oak billy club, capped with a nail-studded brass plate. He remembers this bludgeon: it bit into his knee, shattered his strength, left him walking with a sideways lean.

The club’s grip is tacky. It leaves a red line across his palm. Blood darkens the brass cap, too — blood bristling with ginger hair.

Tom has nothing to lean on in the open cart bed. He takes a long draught of air. Counts to ten. When his heart slows he looks at the burlap sacks at his feet and the billy club in his fist. He can’t open the bags with the driver watching. He can only consider the sign Wheeler has left him, and decide whether it’s real or false.

A night bird calls. Tom does not know its cry. The eiderducks of Oban, the low calls of greylags, are oceans away. Strange creatures surround him. But he can’t go back. Through the long hot summer and wilting autumn he wrote letters to Margaret, full of lies and truths commingled in a fever confession, and he held each one over a candle until the paper whispered into ash. He won’t write to her again. Last week he threw her locket into the river. He is tired of longing for a faraway hearth. Tired of shouldering Martin’s ghost.

A thump shakes the dock. And another. The billy club clatters after.

Favoring his knee, Tom eases out of the cart. He fists the corners of two sacks. With one in each hand he drags them down the dock. They bump and slide and tear up long pale splinters from the aged wood.

“Coming down,” he says, quiet. He does not wait for an answering grunt before shoving the first bag into the barge. The boat rocks with the impact. Silver wavelets form along the bows.

It is a heavy weight, those bones and meat and sinews.

Tom finishes the job in silence.