CE: I’m not a coder, but I read the way that you write about coding, and the agony and ecstasy of it, it is relatable to me as a writer. We go through some of the same processes, trying to translate all the messy chaotic forms of the real world into something that’s linear and comprehensible. I had hoped you would tell me that coding had influenced your writing, because you’re such an elegant writer.

EU: Thank you for that, but the answer’s no. They’re different parts of my brain. There’s one part of me that loves to take apart machines and try to put them back together. The coding part is sort of obsessional in its way, but writing? It’s a different place. I think it goes to a deeper part of me as a human being.

CE: It’s going to sound unrelated to anything we’re talking about now, but earlier you mentioned that when you were a younger programmer, men taught you a lot. It’s very interesting that when there were more women in computing, it was easier to ask for help, because you weren’t the only woman asking for help.

EU: Exactly. I forgot to say that, thank you. I’ve been in projects—consulting projects, with research software engineers—where I was the only woman involved. They told me my job was to translate between the extraordinarily brilliant, and the ordinarily brilliant, and I was to translate for those ordinarily brilliant people. I was abused, actually, I think. Ridiculed when I made a mistake. It was very hard.

When I worked in places where there were more women—actually, my first job was one of those crazy times. You know, with the four people: the art history major, a PhD in Classics, a former Sufi dancer, a French guy who wouldn’t stop smoking Gauloises in the machine room. These were people that I worked with, and because there were women around, I really was able to make mistakes and be able to just feel casual about it.

CE: We talk a lot about diversity in tech. When there’s more people in the room, more people at the table, everyone feels more empowered. It helps us communicate with each other, because we have solidarity with each other in different, lateral ways. In a situation where there’s a monolithic technoculture that’s very specifically masculine, it’s much harder to come into the room and say, “I need help,” or be anything less than excellent.

EU: A woman from the New York Times asked me, “Do you think women have more empathy as programmers?” I said, “Hell, no!” I think women have the right to be as nasty as men. And when that happens, we’ll feel we have equality. The ideal would be that we understand that we need both: the front-end, the people who can design, who can talk to human beings, who can collaborate, who can contact everyone, keep people in touch, keep projects on track; and the back-end, the technical stuff, the algorithm design, debugging. If only they were seen as equals, and necessary!

I don’t know if women are more collaborative, or if we have been taught to be collaborative. Women at Google have complained that, though they have computer science degrees, they’re assigned to front-end development, and those are not technical tracks. It’s great we have these qualities, but the big question for me is, does it put women in a ghetto? Are we stuck in a new kind of pink ghetto?

CE: It’s a very complex question. I hesitate to think that women have a natural aptitude to do anything. I think it certainly feels that way for a lot of people, and I don’t want to invalidate people’s feelings about these things, but I think women have often been pushed into those user-facing sides, because those are the places that were, like, less important.

I’ve read a lot of cyberfeminist writing from the ‘90s, where the first generations of feminists on the internet were talking about how the web was going to be this naturally feminist medium, because it’s all about connection and community. I don’t doubt that it felt exciting for people who were interested in connection and community, but I don’t necessarily think that that’s where we are going to end up.

×

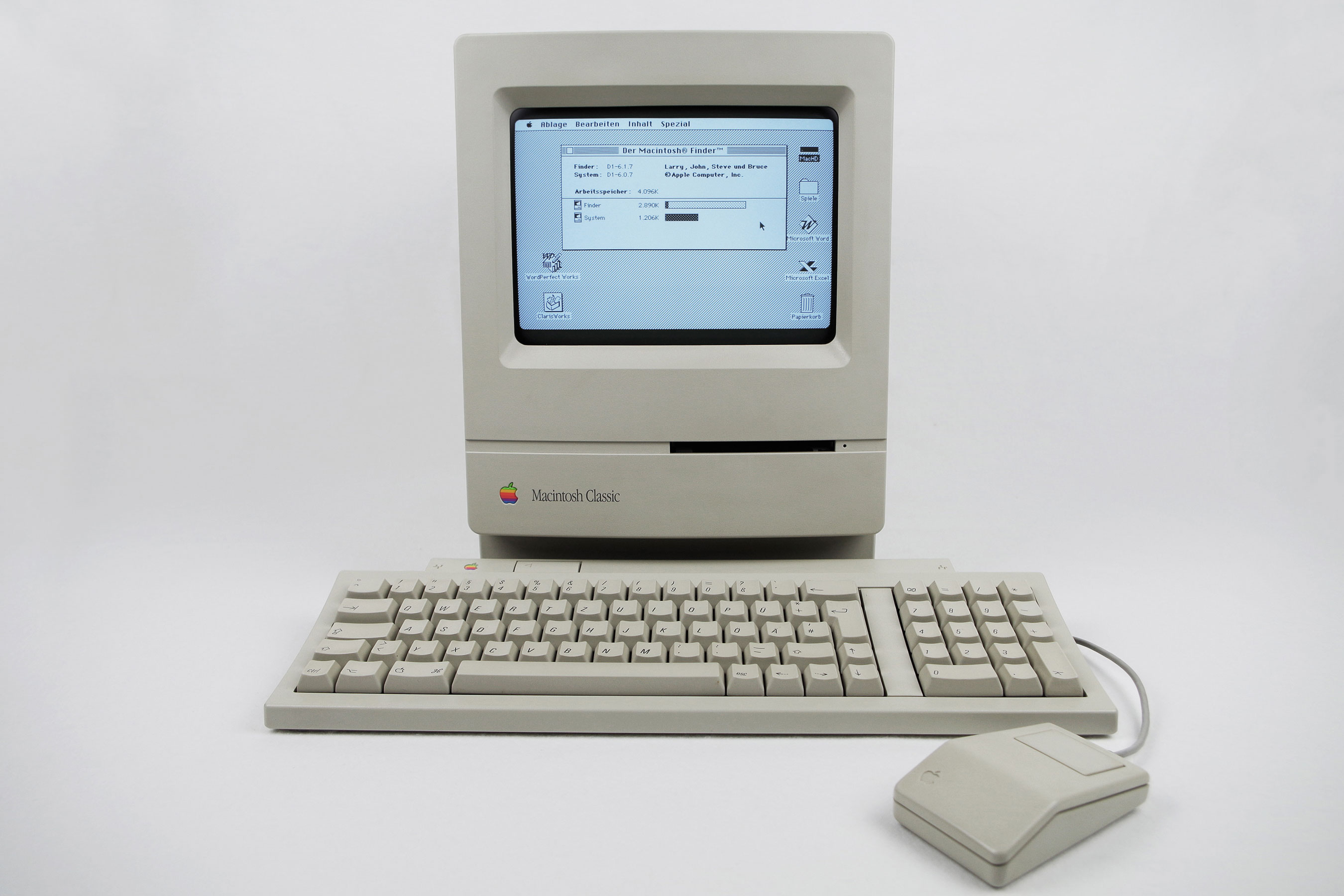

Mac Classic

Mac Classic

TRS-80

TRS-80

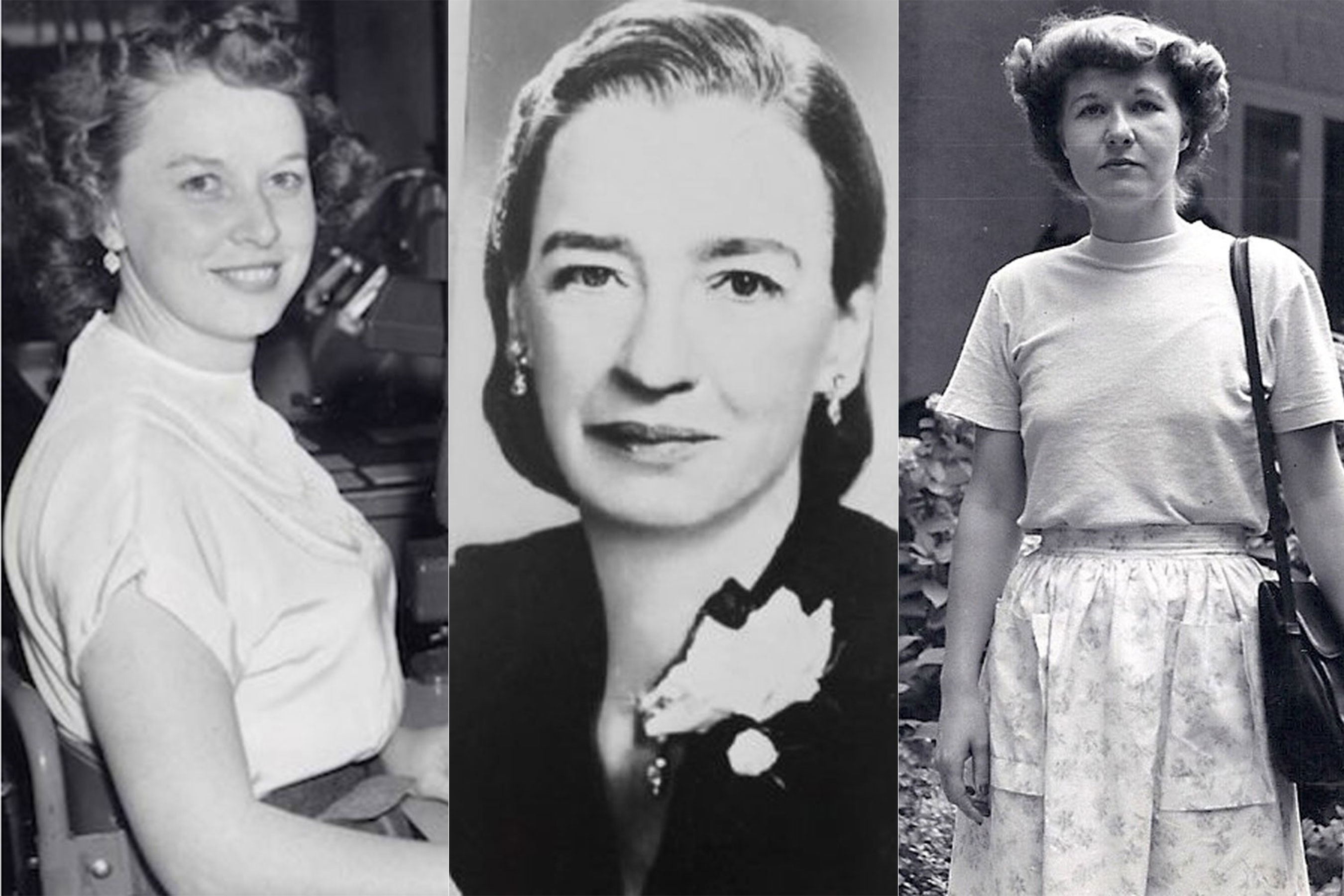

Betty Holberton, Grace Hopper, Betty Jean Jennings

Betty Holberton, Grace Hopper, Betty Jean Jennings

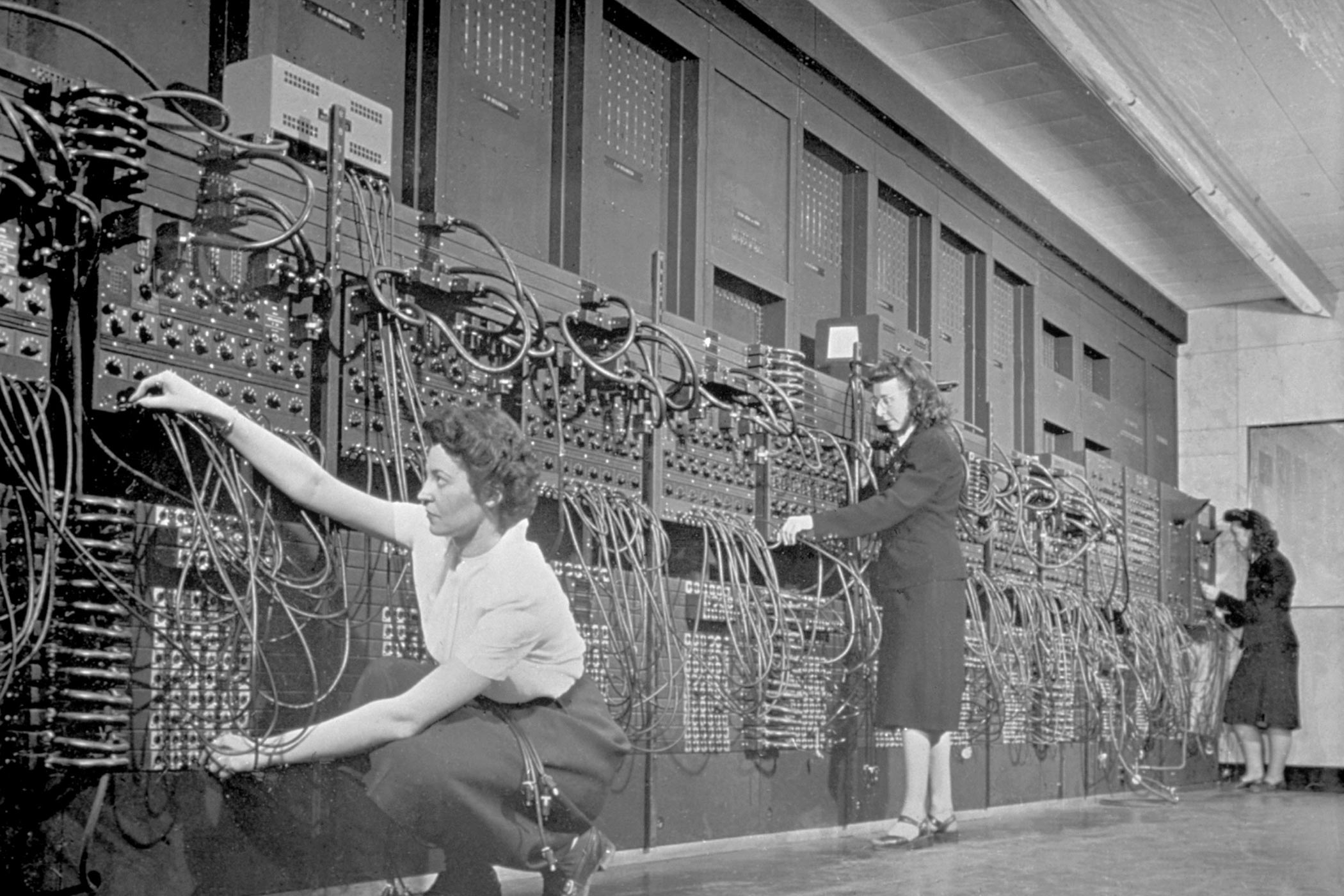

ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer)

ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer)

-

-