Now the iron railing on the second-floor landing collapsed—eaten through by the acrid urine of the animals.

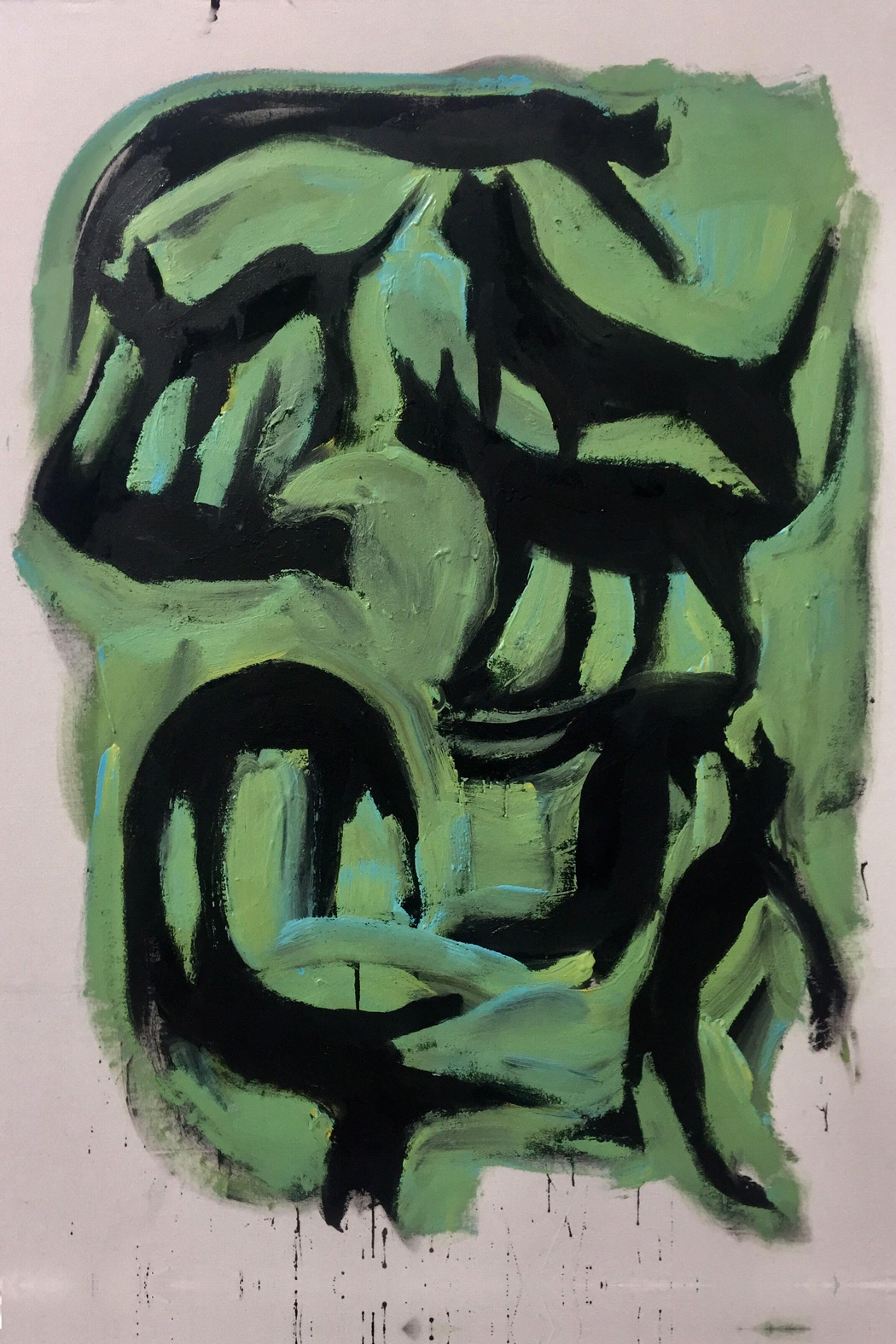

It was profound, metaphysical, psychological. How to describe the stink of her cats? It clamped you like a narrow, feral tunnel, and the woman was lodged so deep she no longer knew down from up. Again she was a girl on a boat with a knife in one hand and a potato in the other. Again she waited while men ate and talked—not to her—when she wandered the dark house at night. The boat heaved. The rough sea knocked her to her knees.

The boy next door was born weak and sick—unable to take a breath. He sucked from a little pipe in his fist. He was like a plant growing where it shouldn’t—tenacious, tenuous.

When the boy entered the woman’s house, it was as if a different boy took his shape. My darling, said the woman.

In the kitchen, the cats twined the legs of the boy while he opened cans on the countertop. He held his breath until he couldn’t—not long.

Outside, the burly vines pushed shoots through window cracks—a green strand bobbed like a question mark above the sink. The boy swatted the slow shit flies that swarmed his mouth.

Here you are, he said, and set her tea where she could reach.

He was the one to find her, of course—dead for a day, they said. She lay on her chintz chair with her hair undone. On each worn arm sat a cat with half-shut eyes. The river brimmed, milky with rain.

Men in hazmat suits cleared the place. They found fourteen live cats and nine dead ones. They cut out the corroded railing and pulled up the floorboards, the subfloor. They crushed the plaster walls to powder—still the smell persisted. They kept at it with the money on their minds.

A funny thing happened then. The boy—the wheezer—could suddenly breathe. A miracle! posited his parents.

No, said his doctor, who soon had a large group of other doctors around him like a gang. No, they said—it was the urine. What came of their research—what help or harm they caused in their labs to cats and asthmatics—that I can’t say.

The boy watched the men trundle the pulverized innards of the woman’s house from its mouth in wheelbarrows. It was like watching beetles clean a corpse from inside out. Later, a rich, unknowing couple bought it and lived a tidy, well-lit life there.

The boy threw his little pipe in the trash. In his fist could now be found a dull gold coin. For luck, the woman said. Or she said, To pay the ferry. Or was it, Beware the evil eye? Beware a man in a black coat? Never trim your hair after dark? Never eat flesh on a Sunday? Never marry a green-eyed girl? Toss salt over your shoulder to get what you want?

On the coin were words he couldn’t read. Instead, he rubbed them with his thumb. He continued to draw deep, powerful breath throughout his life until it, too, ended.