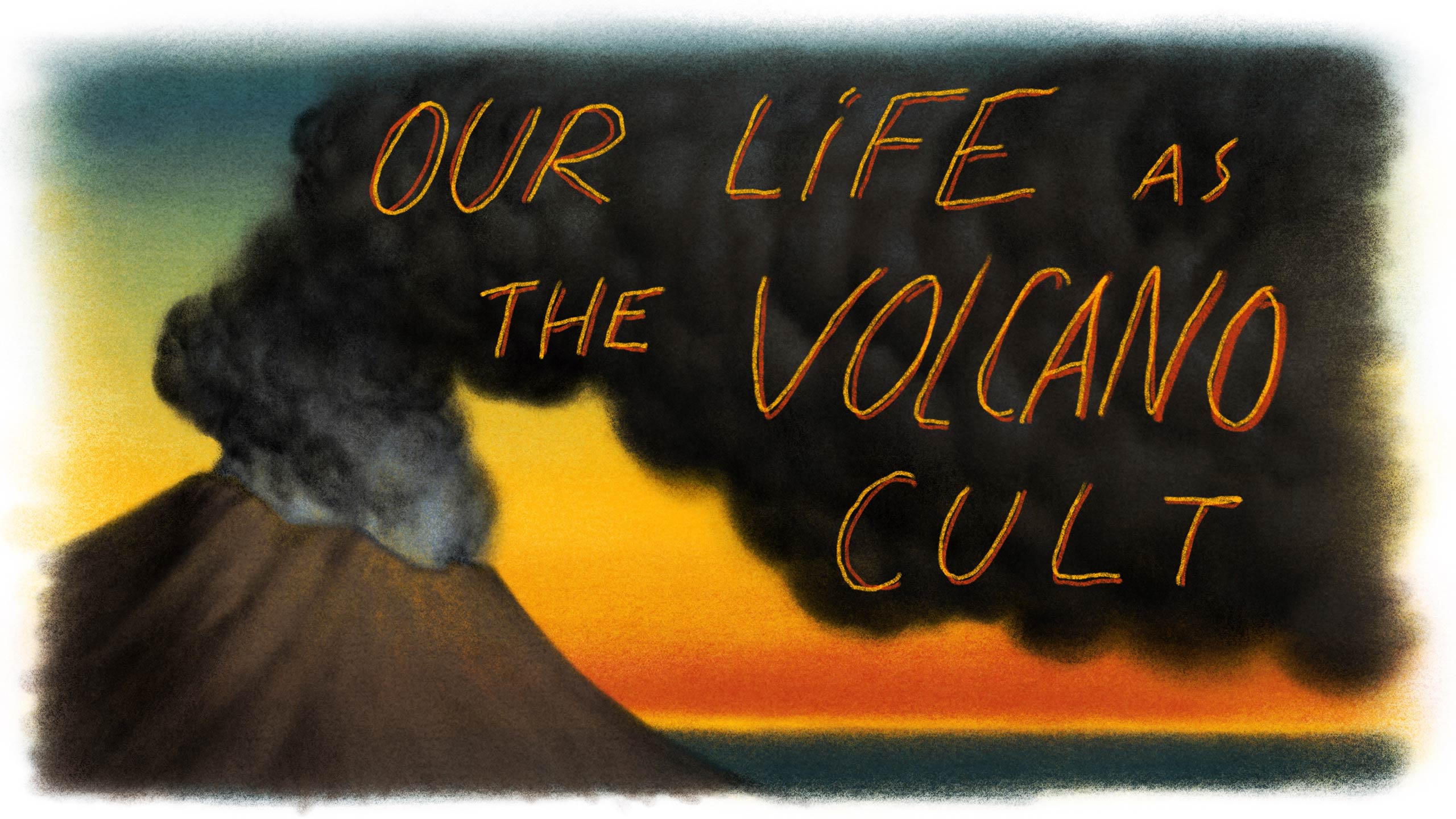

When it was over we admitted maybe it was madness, to have gone willingly to the volcano. After all, we had been warned. There were rumors about what was happening there. But we’d also heard about encounters with those who had joined; serene was a word used to describe them, over and over. Strong. Some spoke about what was being built there, in the shadow of the fire: something new, something better. God knows we needed something better, all of us. And that was why we came.

It was thirty miles south of Hilo where we found her, living among the condemned apparatus of Hawai’i’s only geothermal plant: Rust-freckled girders and yawning turbine halls and cavernous dormitories that stank faintly of egg rot. Everything was concrete, steel, or iron, and every last bit of it was painted green, even the tall round heat exchanger and the pipes that dove two thousand feet into the earth, extracting for electricity the heat that purled in the belly of the volcano. That became our new home. At night we could hear the magma vapors chanting through the wells. At dawn, at dusk, from outside the plant we could see the volcano’s smoke, miles away, horsetailing from the caldera.

First there were ten of us, then twenty, then sixty. We’d tried life the way we were supposed to—obedient wife, content and decent factory employee, loyal brother, perfect bake sale organizer—and if we hadn’t failed spectacularly, then it had been, at best, a sighing sort of decline. We were chumps still trying to sell our way out of pyramid schemes, or transplants from California that were rolled under by Hawai’i’s rising paradise prices, or we were kama’aina whose sagging biceps and sliding cleavage had finally aged us out of the only paying work for brown skin: hotels, tiki bars, construction sites.

But none of that mattered with Yuki. With her we were going to start again in the islands, and this time nothing could stop us.

×

We’d each arrived the same way—wandering under the open arm of the old security booth, into the wide, barely-fenced property of the Plant—and saw a group before us: Women and Men in a rainbow of blank, new-bright t-shirts and khaki carpenter’s pants, bending and sweating through a variety of manual labor tasks. It was like the back-to-school section of a department store had thrown up on a prison yard. A member of the group would approach, smiling, to greet the newcomers. Then Yuki would be called.

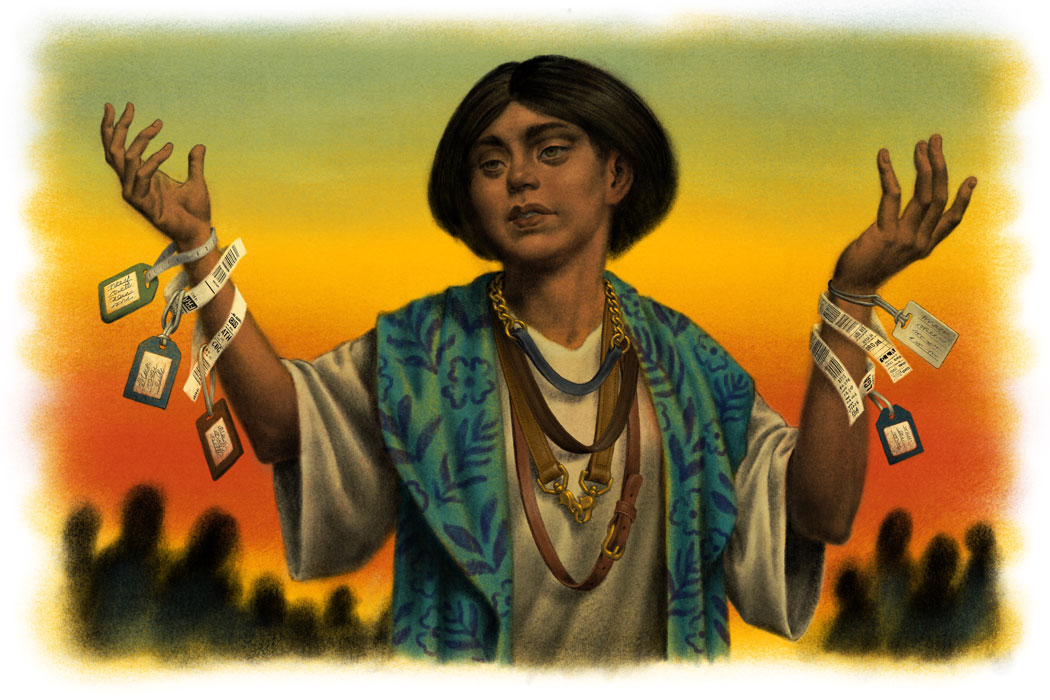

It was impossible not to be struck by her atmosphere. She was taller than many of us, with a spine so erect we were reminded instantly of our own moleish slumping, and her face—clean as a fresh brown egg—sent out a hazel-green gaze that muscled around us, through us, like a river, somehow both soothing and powerful. Over her same-same as us simple clothing she always wore a different robe with bright, colorful patterns, each robe like something haole trophy wives wore poolside we figured, only on her each crease and billow felt a deliberate thing; she owned all the air around her. American Airlines luggage tags and Coach purse straps jeweled her neck and wrists in mad, loose loops.

“If you’re here, I know everything I need to know,” she’d said. “It’s not your fault.”

Or she’d said, “The first Hawaiians, the explorers that found these islands before us. Free in all the most important ways—all the ways you aren’t. But now that you’re here, you’re taking the first step again, the same as the first one they took on the new shore. You’re braver than you think.”

Or, “What they’ve done to you out there, taken your factories and your farms, taken your very knowledge to make. It’s a sickness, it’s a cause, not an end. You don’t know it yet, but you have the maker in you, and the strength to overcome what was taken.”

It’s not your fault.

What they’ve done.

The first step again.

Bravery, strength.

Yes.

And so began our new days, our new schedule: wake-up time, sessions, morning chores, lunch, sessions, afternoon chores, dinner, evening chores, sessions. We worked in groups in the garden or on the plumbing or the electrical, or went backpack hitchhiking to Prince Kuhio Mall to cockroach the things we couldn’t grow or rig, the things we couldn’t afford (our clothes from Macy’s returns piles, blocks of toilet paper from the Walmart loading dock, bricks of non-perishable basics from the Food Bank), we salvaged everywhere along the way and back. But over all of this there was the fever of sessions—the times in which Yuki came to us and forced us to grow. No telling when or where she would appear, only that she would, and that it would hurt.

We’d be taping the wiring for the solar panels, or drafting water from the freshwater pump, when she’d suddenly be standing in front of us. She’d take our small work detail—five or six total, maybe—to the heat exchanger closet, have us stand in a ring around the extraction pipes that were charged with steam from the volcano’s chambers, and say, “Imagine four hundred thousand years of change, the earth exploding and starting again, ruining and repairing itself with fire. That’s the inside of a volcano. Now,” she’d say, opening one of the release valves, “I’m going to let it fill you up.” We took deep breaths, found walls to lean against, anything to avoid passing out in a damp pile, our skulls throbbing as the heat and steam increased to unbearable levels, our lungs gasping on nothing but oven air.

Or she’d come upon a gardening group, peel off our unraveling gloves, and start a long hike with us in the noon heat. Our knees would be chewing with ache, our backs weary from the rocks we’d each be tasked to carry. All around us the scraggly, veinous trees and clusters of weeds were blooming in purple and yellow and green, the coffee-tinted soil besides. “It’s a noisy world, the newspapers and magazines, the commercials and radio stations, the emails and text messages. Opioids of the mind, and you have to take them, because they’re everywhere. But here we can finally escape even our own minds.” Yuki explained. “What else is a marathon runner’s high? Aborigines went on walkabouts, Iroquois induced fasting visions. We’re no different.”

And time and again she was proven right. At every session, while most of us were fainting or crawling into corners or trying not to yak up our shoyu rice breakfast, someone would be standing in the middle of the collapsing group, saying, “Okay, oh, this is it,” or, “Oh, my God, I can feel it.”

Yuki would approach that individual, palm their cheek, and speak to them, only them. Words of praise and admission to the next level of understanding, while underneath, the rest of us tried not to die.

Later, we’d ask the lucky one how it had felt. They smiled; but they never had words for it, could only shake their heads, shrug with hands upturned towards the ceiling.

It was hard to argue with that, or the praise that came from Yuki afterwards, the way that individual seemed to shine with a new light under her gaze. Someday it would be our turn. We imagined our bodies flooded with ecstasy, a moment of tasting the other side; at that moment, we told ourselves, her gaze would lock on us. Was that soaring, expansive minute in the latest session a signal of hypovolemic shock, or was it (please please please) finally our time? Was that spangled high from malnutrition, or the (yes, yes) evacuation of our former lives?

One of us asked, “She’s always watching, isn’t she?”

Another answered, “Yes. Be careful.”

“Otherwise what?”

“They say only the best get to go with her.”

“Go where?”

“She’s been inside the volcano.”

“Impossible.”

“Only the best will go.”

We always felt it, the volcano. The caldera, the fire, the tremors from ongoing eruptions. The shifting of continental plates beneath us.

×

We remember the day Damien and Kailey arrived, a father-daughter combination. Damien, clothed in a pitstained red-and-white aloha shirt and threadbare khakis, his brown Hawaiian scalp showing through thinning black hair. And there was Kailey, six years old, dark as a surfer and impossibly clean but for her ashy knees. Her woolly hair was crimped into a ponytail, her eyes all shine.

“We heard there was maybe one place for us here,” Damien said, his pidgin thick. How country, we thought and whispered later, some of us having already forgotten it wasn’t long ago that we talked just so, before we started parroting Yuki. We smiled and took them to her.

Obviously it wasn’t our first time with new arrivals, but it was our first time with a child; we figured it wouldn’t be that different. Maybe the child just wouldn’t be part of the most brutal sessions; we didn’t know. Only that Yuki would show us how. We added Damien and Kailey to the work rotations.

Later, out of earshot of the arrivals, someone said, “They seem hard up.”

“Same-same as everyone,” another answered.

“I don’t know about that.”

“What?”

“Maybe they won’t make it.”

“Everyone makes it.”

“Yes,” someone answered, “Yes, that’s true.”

×

That was how we knew Yuki was right, that this place was right. Because we were getting stronger, we could feel it. Not just physically, but spiritually, too. Our sessions were longer, ever more painful: Yuki had us walloping each other about our bony edges—shins, shoulder blades, spines—with flat boards until we were swollen and blue-black, slicing long tick marks into our forearms (“Think of all the people that have been hurt this way, killed this way, on the edge of a blade,” Yuki would say, “When we do this, we touch them, we keep them, we learn their world in a way no one else can.” And she was right, she was right). But the more we hurt our bodies, the less they were our bodies, and the less they were our bodies, the more we felt ourselves boiling down, like rocks into lava, one into the other.

It was most obvious when we left the plant on backpack trips to thieve. Hilo, the mall, there were so many unnecessary lights, so many objects pandering to (encouraging, even) the weaknesses of people—their inability to sit on a seat without a cushion, the massive portions of syrup-doused foods they didn’t grow or catch or cook, electronic screens pulling eyes and minds away from the here and now, the sonic waves of tinny, hyped music crashing against each other in the mall walkways, the (always, always) brown-skin service workers—we couldn’t remember, had all this been us? This plodding across parking lot after parking lot, this constant dulling entertainment, this sag into the thick sleeping bags of bodies made more faithless everyday?

It wasn’t us now.

At The Plant, the days went. The gape of our dormitory ceilings, the cool abandoned corners of the many iron-girded rooms, the half-finished industrial kitchen we’d rigged with milk crate cupboards, the pump water that tasted faintly of coins. The lava black fields and the sinewy-new forests among them. The wheeling of the stars in the volcanically pink dusk. The shift from one week into the next.

Damien and Kailey became a problem. While we’d each found our place in the group fairly quickly—such that it got to the point where it was hard to remember what the group looked like before each of us had come—Kailey and Damien didn’t seem to take the hint. For example: Damien worked about as hard as a bulb of taro. Whichever team he pulled work detail on, you could feel the rest of the team’s sighs blow through the whole Plant. He’d take twice as long to shovel a fourth as much, grunting loudly the whole time. He constantly dropped wet clothes before they made it to the clothesline. He was unable to pump a gallon of water without drinking a cup, picking at the sweaty seam of his pants, suctioned into his butt crack.

And whose snort of derision did we hear in the back row when Yuki was leading a session? Who eked out the last of every minute in bed, barely making it to morning rotation? His body didn’t reassert itself the way ours had, revealing ropes of muscle and newly-tight skin; if anything, Damien went the other way, like a bear getting ready for winter.

And as for Kailey. At first we were excited to have a child at the Plant, but then we remembered what a pain in the ass kids were. Surges of ridiculous energy at the most inappropriate times—bedtime, or post-session when our bodies were wrecked and she’d been sitting idle, or just as we were coming off evening chores, our brains stung with exhaustion—plus the extra twenty-five minutes it took her to get any tasks done, between her rivers of questions and lack of adult body coordination. Also! The moods: she could go almost instantly from bouncing happiness to a strange, tucked-away silence as cool and slow as sap. Some of us who’d been around children before explained that it was normal, this was part of the apocalyptic storm of body chemistry common for the age, but still. We did not sign up for this.

Then there was the first time Yuki had selected Damien for a session. We were delirious from a week of fasting, our bodies torpid and heavy with nausea, when Yuki stood before Damien and the rust treatment crew and said, “This time, the scab lands.” We weren’t on the rust treatment crew, but we left the garden rows, the laundry, the solar cells, all our tasks where they were, and followed. Normally this wouldn’t be what we’d do, treating a session as a circus. But this time, who could blame us? We passed between the draping Hapu’u ferns and the muscles of the ‘Ohia trees, then tramped down a thin path to the scab lands, a field of cracked black plates of volcanic rock.

Damien was called to the front and stood. He didn’t seem to be wobbling like the rest of us.

“Tell me,” Yuki asked. “Damien. What is changing in you, now?”

He cleared his throat and simultaneously flatulated with a rubbery flap.

“Sorry,” he said. “Eggs, I think.”

“You’ve been fasting,” Yuki stated.

“Sure,” Damien said.

“I know you haven’t been here as long as some of us,” Yuki went on, “But I wonder what’s changed, for you.”

When he was silent, she said, “Think, then, of what you’ve left behind.”

We heard what he’d left behind. He’d been married, that much we knew, and we could only assume his wife was the bread-winner. Something about management and hotels, and that they’d had some ocean-facing three-story in Puako. Then the wife was gone, a car accident. There were always drunk drivers on the Kona roads, we knew this too; we’d been some of them ourselves. Clearly, Damien hadn’t done well with whatever remained after the accident. And we understood that, but he’d corroded our sympathy pretty quickly with his complete lack of anything redeemable.

Yuki repeated her question.

“Nothing,” Damien said. “I didn’t leave nothing behind.”

“Perhaps you can now,” she said. She gestured out to the scab lands, to a section where the a’a lava was thick, all friable spikes and upturned shards. “Take off your shoes.”

But he didn’t. Yuki appraised him for a moment, his still-shoed feet. Then she turned to the rest of us. “He’s not ready yet, I understand. Who among us is ready?”

We hesitated, but Naomi stepped forward. Naomi from O’ahu, Punahou prep school, Naomi who’d failed to make anything of herself but a middle-school substitute teacher, at least until she’d improvised a lesson about teenage sexuality that included the phrase “squirting the white she-she sauce.” After that, she was reduced to part-time work at a gas station.

She’d shucked her office flats and stepped gingerly onto the lava claws, breath catching in her throat, back hunched and flinching with each step. It went about as you’d expect, like a dull blade against tomatoes. She whimpered, but continued, feet skating and slippery with blood when she reached the relief of the flat sections.

How could we remain standing where we were? Naomi was there, quietly, and one by one we followed, mostly because she was one of us, but also because we didn’t want to be left behind. As we were opened against the earth, Yuki throated out a Hawaiian chant to the volcano goddess. Damien stood watching in the sunlight, sweat mustaching his upper lip. It wasn’t the last time he’d sit out a session.

×

“He’s not going to the volcano any time soon,” someone said after coming off garden duty with Damien. “He couldn’t empty a bucket if the directions were on the bottom.”

“But he’s been talking. People have been listening.”

“About what?”

“He says Yuki is wrong. That we’re never going to the volcano and she’s just using us.”

“He doesn’t understand,” someone said, and others agreed, although something didn’t feel as strong this time.

Other things were changing, too.

“Yuki’s building a dollhouse,” someone said.

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“They snagged parts of it from Walmart during last shopping rotation.”

“Plus the ‘uke.”

“What?”

“The ‘ukulele,” someone clarified. “We heard her playing it at night, tuning it up. People are saying Kailey was in there with her.”

Picture Yuki on her hands and knees, snapping together the pink-cupcake walls of a duplex dollhouse, or humming out top forty tunes to the soft-sad chucking of the ‘ukulele chords.

“No way,” someone said.

“I heard it,” someone else claimed. “I did.”

×

And yet it was hard to believe something wasn’t happening. Damien’s work rotations, as dictated by Yuki, carried him farther from the interior of The Plant: outer fence maintenance, new garden breaking, perimeter lookout. Many of the jobs required long walks and extra exposure, things even Damien figured were probably bad for Kailey. Which we resented. Because there she was, back at The Plant, getting in the way of things.

Days like that we’d see Yuki outside and our bellies would go kapakai with anticipation of the coming session—(we’re going to feel it, we’re going to feel it)—only there Kailey would be, arms length away as Yuki came upon us. Still, we gathered up for the session, same as we always did, a loose group with stiffening backs, readying ourselves for ascension.

“Take a moment to close your eyes,” Yuki would say, and then something to the effect of, “See a fire. In fact, see all the fires. Do you see them? See as well what’s burning in them. What is the difference between what’s consumed and what isn’t?”

We’d try that, our eyes closed, the ribbons of flame, buildings and forests and cars consumed, or if it was another suggestion of visualization, we’d try that, too. But she’d never say anything more and after what felt like hours we opened our eyes and she was in the distance, Kailey following alongside, the pair examining Lehua blossoms or tracks gamy lizards were tapping into the dirt.

“Are you fucking kidding me?” someone said.

“Was that our session?” someone else asked.

×

There was word going around that Yuki had been found in the kitchen one afternoon, at that hour when most everyone was finishing the last of the day’s outdoor chores. Yuki’d held a loose stack of three Spam cans in one hand, her other holding a Tupperware bowl of cold food bank rice. Maybe she’d started, even, when the person had entered the kitchen. She was in the process of handing the food to Kailey.

Whoever had walked in on her hadn’t said anything, is what we heard; Yuki hadn’t said anything either, just went on giving Kailey the food, the young girl then leaving. We could imagine the last moments of that encounter, when Yuki went from a crouch back to her full height like a switchblade. But no words, or none the rest of us ever knew.

Three extra cans of Spam, extra rice. To a girl who was already eating better than the rest of us, to girl who wasn’t doing a tenth as much work. It wasn’t the food that was the issue, or that was what we told our roaring bellies; it was the fact that we could see something happening to Yuki, an unclenching from her vision of what we were building, replaced by something simpler. We all knew it wasn’t hers to claim.

×

When we were asked later, in the interviews, about what happened, we all said it the same: we couldn’t go on that way forever, with Damien. So it was the week he pulled garden duty with Kapono, when it happened. Garden duty mostly involved convincing yourself you could tell weeds from food, and occasionally being confident enough to purge something, which is what we guessed Damien and Kapono were doing when the fight started. Others were working outside, whether wringing ropes of clothes to hang or doing leak patching on the heat exchanger roof. So we heard it coming. It’s hard to say why no one did anything sooner.

“You dumb nut,” Kapono was yelling at Damien. “You couldn’t find your ass with both hands, yeah?”

Damien said something back.

“What?” Kapono said. “Try say it again.”

But there was no reply.

And a bit later, Kapono hollering one more time: “No, that one, he like go

over there, I said.”

Kapono slang his pidgin like the rest of us when we wanted to feel a bit loose, so it was easy to forget his story: He’d left the islands for Chicago, the cool fury of derivatives trading; he’d returned with the gone years of a wrecked marriage and a bank account he’d bled in failed real estate speculation. He still had the gods of Fiduciary Duty and Quarterly Earnings whispering in his ear, and so didn’t hesitate to tell us how to do our jobs. But his heart was in the right place, and anyway, he was working on it.

Now we heard the clang and scrape of shovels attacking each other. Both men were grunting and cursing. We dropped what we were doing and came running.

By the time we reached them they’d left off the shovels and Kapono was on the ground and Damien was staring at a knife that had been inserted into his belly. There was a blossom of red blooming around the hilt.

“Damien’s not feeling right,” Kapono explained as he scraped himself to his feet, having been pushed, apparently, by Damien.

“You think?” someone asked, as Damien sat down suddenly, awkwardly, as if he’d recently completed a long race.

“He said,” Kapono started. He was red-faced and panting from exertion. He waved in the vague direction of Damien, who had lain down as if to take in some sun. “He said that I smell like dog tits.”

“But you do,” someone said.

“I know,” Kapono said, sounding desperate. “But come on. He wouldn’t do anything. He was telling lies about Yuki. You know how he is.”

We did know how Damien was.

Yuki arrived, holding Kailey’s hand, but the girl detached immediately and ran to her father’s side, calling “Dad? Dad?”

Some of us had been trying to start first aid, to get Damien’s shirt off, but had stopped when it was clear the shirt was tacked down by the knife. With Kailey there, we suddenly felt like accessories, and so a few of us started back towards the body, to pretend we knew something about how to fix it.

“Can we get it out?” Kailey asked, her voice wet and up octaves. “We have to get it out. Let’s get it out.”

“No,” Damien said, batting her hand away with his own.

“Dad,” Kailey said again.

“It’ll only hurt for a second,” someone offered.

“Yuki, Yuki,” Kailey said, and she was doing this weird thing where she waved her hands and bounced from one foot to the other, then clutched at Yuki’s robe, “Let’s get it out.”

“Everyone please be quiet,” Yuki said, crouching at Damien’s side. Her robe, a light ivory color, glided across his wound, and we knew that cloth, clean up to now, was going to come away stained.

“Some kinda bad joke, yeah,” Damien said, “I gonna die like this.”

“Yes, Damien,” Yuki said, slowly looking him up and down, not in any sort of hurry. “You will die, someday. But not like this.”

“I don’t want to,” he said.

“You never do,” Yuki said sadly. “You’re almost there, aren’t you?”

She leaned in close to Damien’s ear. His eyes were all across the sky and his legs had started heel-scraping the ground, as if he could back away from it all.

Yuki whispered something to Damien. We all strained to hear, but got nothing. His legs started slowing down.

×

Yuki didn’t pull the knife out, knowing that impaling objects are better left in, but that didn’t save Damien. We’d wrapped the wound, knife and all, and transported him to a mattress, but that didn’t save Damien. For those first few hours we took turns tending to him—washing the edge of the wound, hydrating him and medicating him, careful as mothers—but that didn’t save Damien. What saved him came after, from the outside, came with boiling red and blue lights and a shrieking siren that carried over The Plant, a sound we’d heard before, although never here, and never like this. It filled the architecture of everything we’d done since arriving, the concrete we’d bled into and the rock garden walls we’d raised with our raw hands, the guts of electricity and water we’d stitched back together, the food we’d grown to harvest, the whole previously condemned geothermal plant we’d proven was capable, if only it got the right attention, of thriving.

But those sirens—we couldn’t believe how quickly this was all being taken away. Someone had called someone, and now there would be things to answer for. Maybe it was Kapono, who’d disappeared in the aftermath of the stabbing. Maybe it was one of the others, the few who’d also taken flight in the hours since. Whatever. What mattered was that we understood what was coming and we needed to know what happened next. So we did what people always do, we searched for our leader, and found her in the field just outside the dormitory. Kailey was with her. We kept our distance.

They weren’t speaking at the time we arrived, but maybe they’d been silent perpetually after the whole you-didn’t-stab-my-father-but-you-might-as-well-have moment had asserted itself. They were both staring back toward us, only above us, at The Plant’s upper floor where Yuki’s room was. It felt as if they’d been staring for a long time. Yuki was crouched at Kailey’s eye level. She passed a doll to Kailey, an astronaut is what it turned out to be, which we saw when Kailey passed us, back to her injured father and the coming emergency vehicles.

Yuki paused, a series of breaths, while the sirens filled everything and bounced around off the trees and ground, the air. She turned her gaze from The Plant and returned to us.

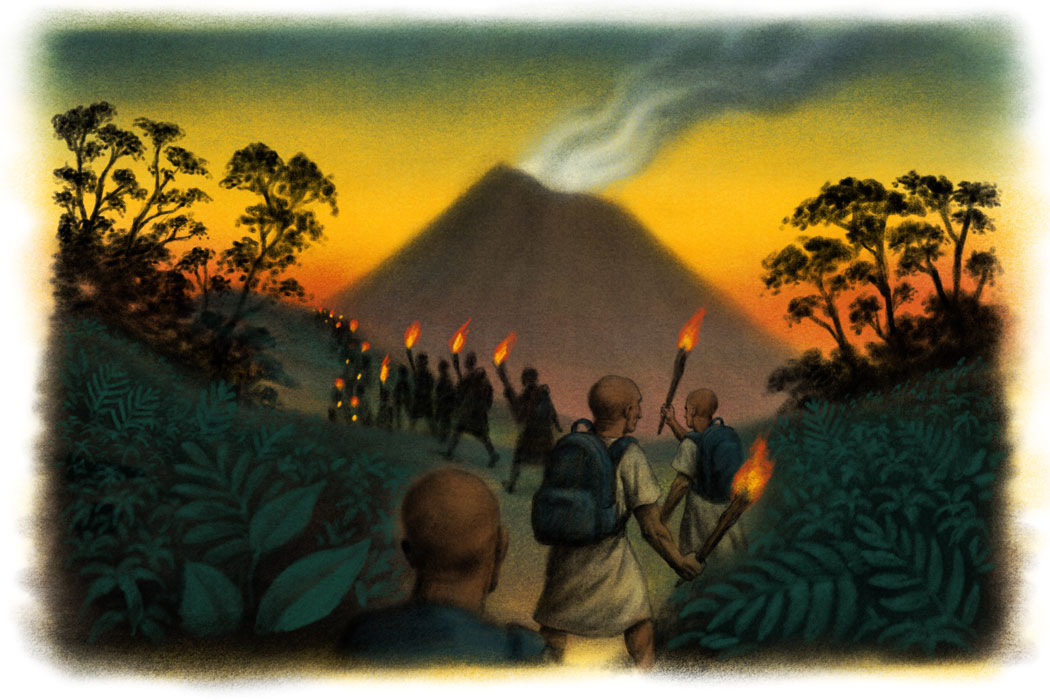

“It’s time,” she said. “We’ll have to go farther.”

There was a decision that occurred. Yuki didn’t ask it of us, and we didn’t choose it ourselves. It was only that we realized which of us would go, and which of us would stay, a truth which arrived as if we’d always known it. We finally understood what it felt like, success in a session, because as we all stood there in recognition of what was coming and what it made us, it was as if we opened our chests and saw our true insides.

All at once there was a rising.

Oh, was what we thought, what we felt: Oh.

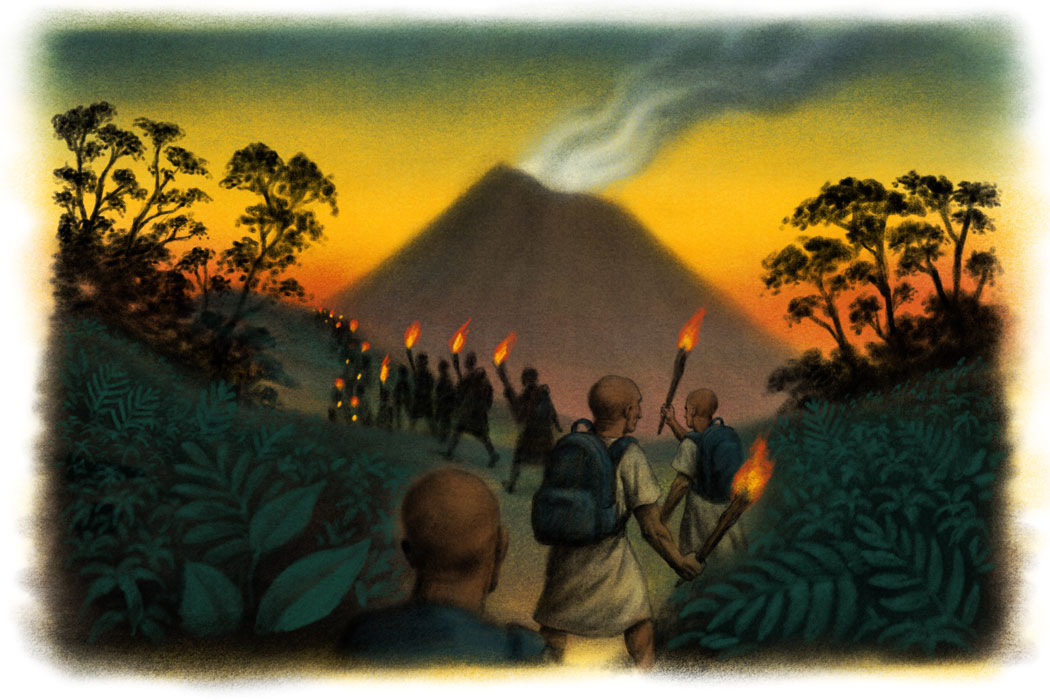

And when it passed, the one group—the one that was going with Yuki—slipped from The Plant even as the sirens and the lights arrived. Their backpacks on their backs, Yuki in the lead, eyes fixed on the burning distance, the volcano. The rest of us remained, ready to greet The Plant’s final arrivals.

It’s not what you might think, for us to remember it all now. The sessions, the hunger: we have nothing but gratitude. Times now when the volcano is at its most ferocious, when the news helicopters fly over and broadcast the churning insides, the magma howl, that’s when we feel the others strongest. There’s a brightness that runs inside us now, hot and steady as lava, and try as you might you miserable modern world you’ll never put us out.