“Dark, seductive . . . Noirish and sexy, this provocative novel explores what it’s like to be a woman on the edge.” —Adrienne Westenfeld, Esquire

“[A] crispy biscotti of a novel . . . You’ll feel indecent reading it in public.” —Molly Young, Vulture

A trip to Italy reignites a woman’s desires to disastrous effect in this dark ode to womanhood, death, and sex

To cool-headed, fastidious Pricilla Messing, Italy will be an escape, a brief glimpse of freedom from a life that's starting to feel like...

There is a sweet anguish to traveling. The trip you planned for months, maybe years is suddenly here. You’re on the plane, you’re taking off—the adventure is ahead of you! But it also means, inevitably, there will be a return flight. It means the clock is ticking. So many days are spent just getting by, and that kind of day drags on. But now, when you most want time to slow down, suddenly it speeds up.

I had this paradox in mind when I was looking for where to set The Worst Kind of Want. I wanted to heighten this sensation. Cilla flees a plodding existence caring for her ailing mother in Los Angeles, for Rome, where she’s confronted with centuries of history, layers and layers. There’s no denying how brief and fleeting a lifetime is when looking at the crumbling ruins of a city that flourished more than two and half thousand years ago.

On a recent trip to Italy I decide to retrace Cilla’s journey through Rome and Puglia, with a Fujifilm Instax Wide 300. Cilla more than anything wants to hold onto something that, in its nature, is ephemeral. She wants to stop time. As an object, a polaroid is the closest thing I can think of that mirrors Cilla’s desire.

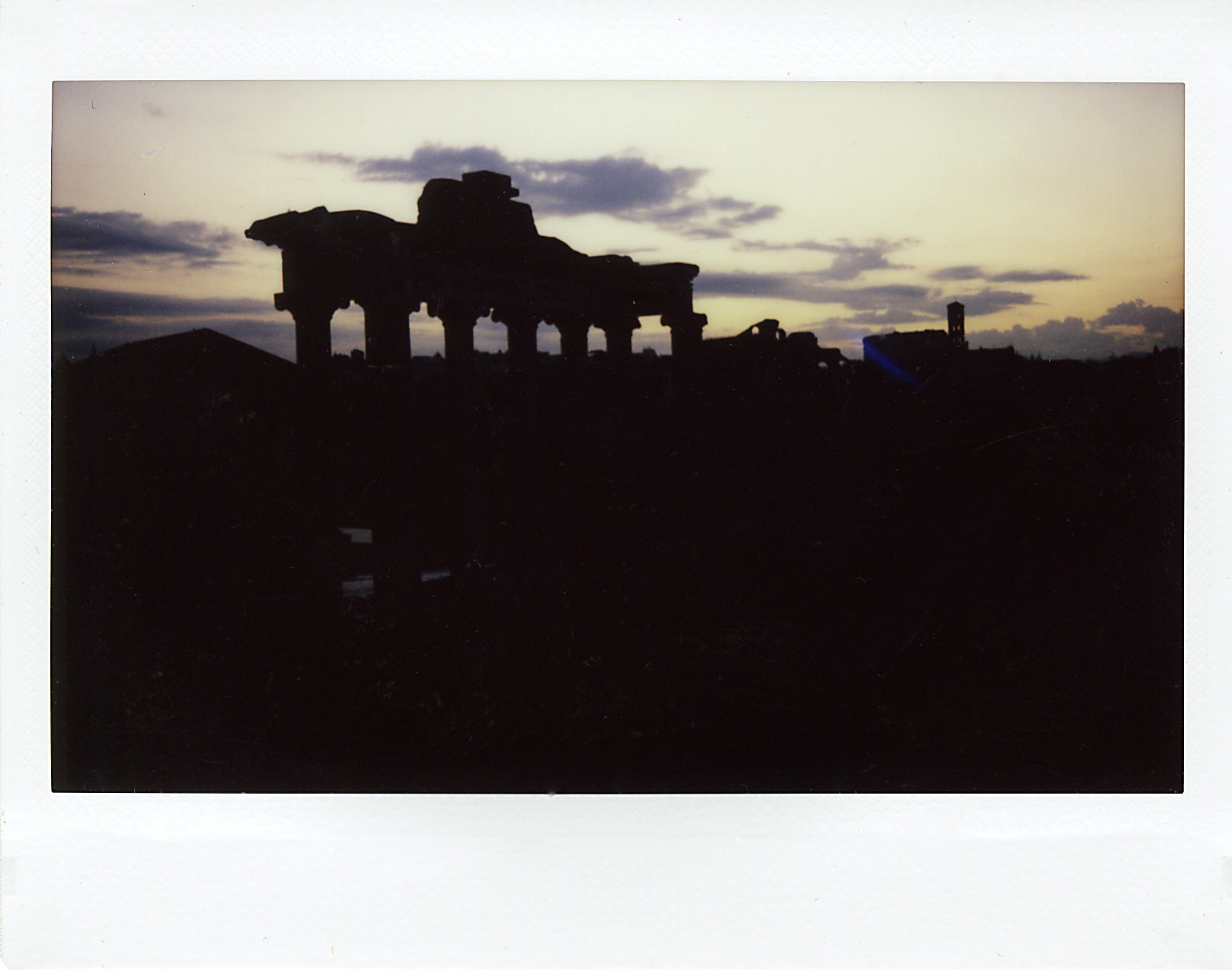

I wake before dawn, still jetlagged, and hurry from the Airbnb in Trastevere to the Forum. At that hour I know this place—which once held triumphal processions, saw elections, criminal trials, and gladiatorial matches—will be completely empty. I’ll have it all to myself. It’s easier to attempt time travel if there aren’t millions of tourists to distract you. Only a few seagulls and pigeons, several sleepy polizia nearby, wondering what the hell I’m doing. Trying to make it feel real. The columns of the Temple of Saturn are the only discernable object, one of the oldest monuments in the Forum.

I wake before dawn, still jetlagged, and hurry from the Airbnb in Trastevere to the Forum. At that hour I know this place—which once held triumphal processions, saw elections, criminal trials, and gladiatorial matches—will be completely empty. I’ll have it all to myself. It’s easier to attempt time travel if there aren’t millions of tourists to distract you. Only a few seagulls and pigeons, several sleepy polizia nearby, wondering what the hell I’m doing. Trying to make it feel real. The columns of the Temple of Saturn are the only discernable object, one of the oldest monuments in the Forum.

I walk from the Forum to Aventine Hill, one of the seven hills in Rome. From here I can watch the city come to life. Taxis and commuters begin to congest the Lungotevere, which wraps around the Tiber River. It’s near this stretch of road that Romulus and Remus were plucked from the waters of the Tiber. In the blurred distance I can just make out the chariots crowning the top of the Altare Della Patria.

It’s still early enough that the Circo Massimo is only half-lit. Once the largest chariot-racing stadium in Rome, it could hold 150,000 spectators, but this morning—which has turned chilly, a sign that summer has ended and fall is approaching—I am the only one here.

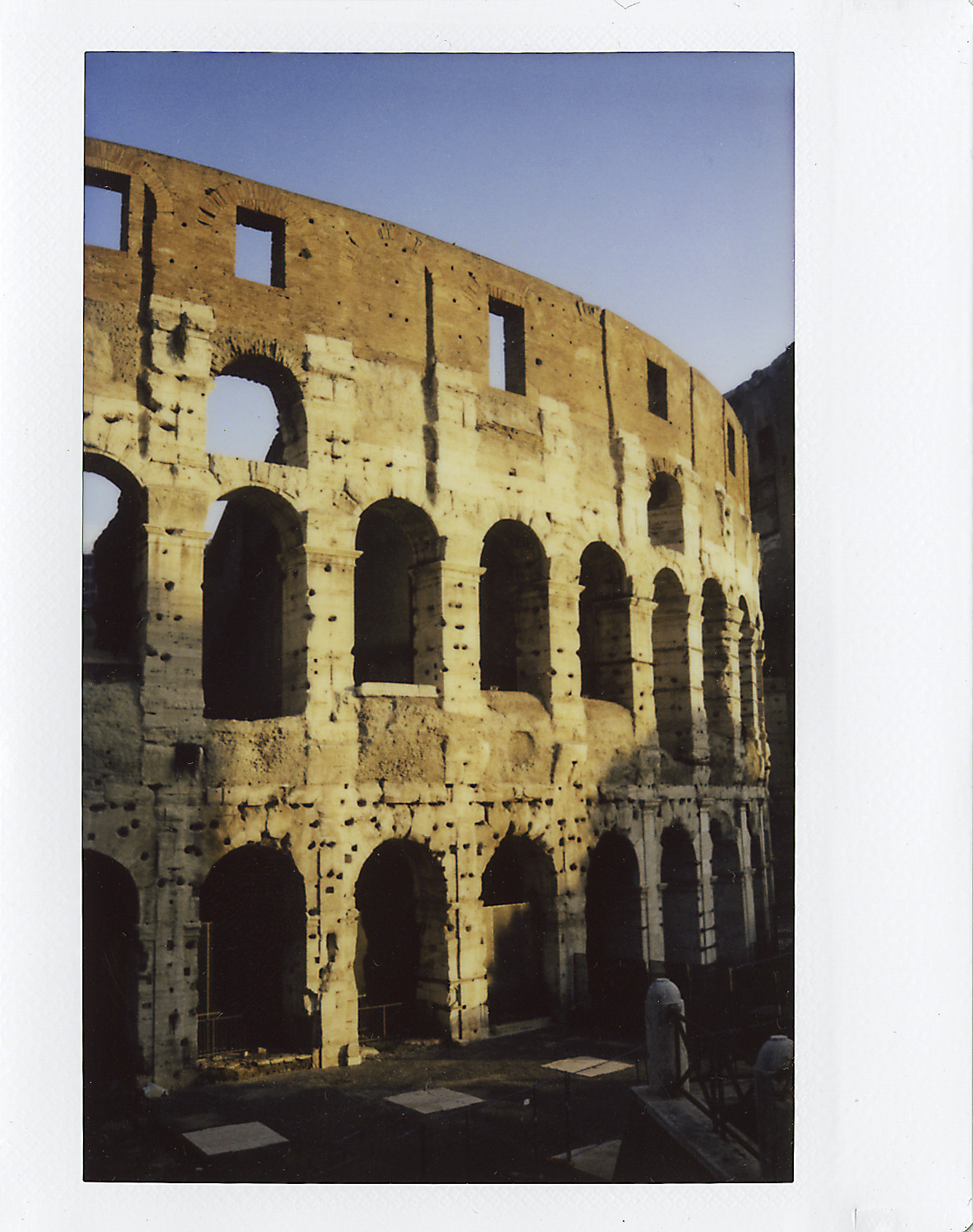

Rome’s ancient ruins hold so much space in my memory from films and books and paintings, that whenever I see them in person I struggle to believe they’re real. Standing in front of the Colosseo I try to imagine gladiators fighting for glory, or those condemned to death who were sent out naked and unarmed to face an animal that would rip them apart. Even with the site empty of Carabinieri and tourists, street vendors and hustlers, the sun finally risen, I still can’t quite fully reach across time and grasp it.

I decide to drive to Puglia this time, rather than take the train. I want to see how the Autostrada connects the cities and towns. I want to drive the highways that follow the ancient roads. Outside Rome it turns flat and agricultural quickly. It’s surprising how much the landscape resembles California. But then rows of olive trees begin to dominate the valley, a sign I’ve reached Puglia.

There’s no denying the romance of a masseria. Built as monasteries, or summer mansions for noble Neapolitans, many have been turned into luxe bed-and-breakfasts. Imposing and exotic, with overgrown bougainvillea weaving between citrus and olive trees. The Adriatic so close at night you can smell its salty perfume. Being here means my trip is already more than half over. Time seems to speed up even more. I push myself harder, eating and drinking everything, waking up at dawn and staying up late.

There’s no denying the romance of a masseria. Built as monasteries, or summer mansions for noble Neapolitans, many have been turned into luxe bed-and-breakfasts. Imposing and exotic, with overgrown bougainvillea weaving between citrus and olive trees. The Adriatic so close at night you can smell its salty perfume. Being here means my trip is already more than half over. Time seems to speed up even more. I push myself harder, eating and drinking everything, waking up at dawn and staying up late.

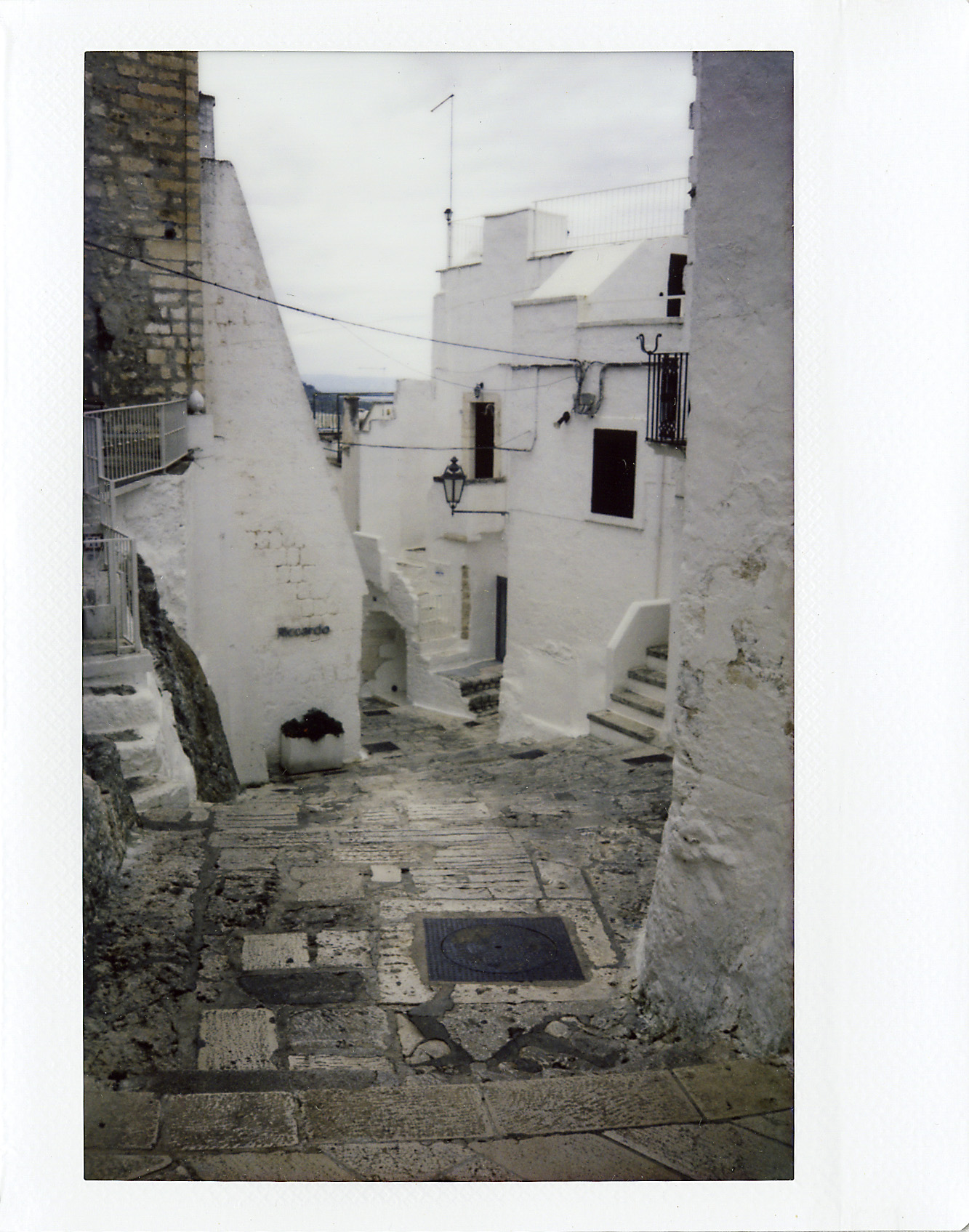

Nearby ancient towns cling to hillsides. This is Ostuni, known as La Città Bianca because of its whitewashed buildings and monuments. Its paths are intentionally labyrinth-like to confuse invaders. Some narrow or dead-end, others open up to views of the Adriatic, so piercing and cobalt blue it hypnotizes. This is a place where you can get lost.

Or find a kitty.

In the summer, seaside towns like Torre Canne swell with tourists. The atmosphere is bacchanalian. I’m visiting at the end of the season, the very last weekend many of these restaurants will be open, which is my favorite time to be here. I like to imagine the many dramas that played out over the summer—the dance parties on the beach until dawn, overflowing with giddy Italian youths looking to have a good time. I breathe in those sea views, eating grilled octopus with a bottle of Fiano.

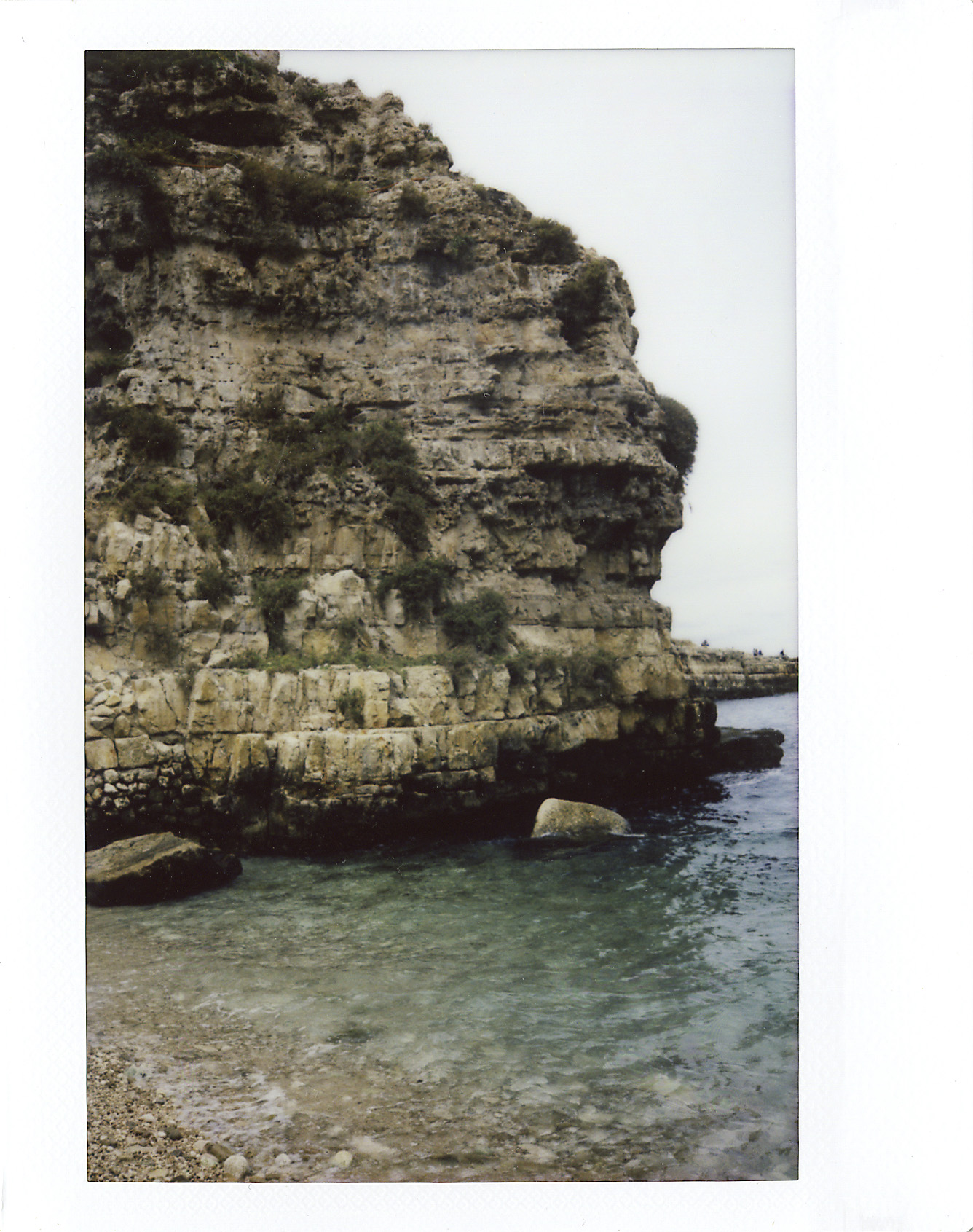

Just a few weeks earlier this would have been a bustling bar serving capicola sandwiches, taralli, and Peronis. Umbrellas and chairs available for day rentals; oiled-up bodies roasting in the sun; tanned tourists smoking cigarettes on the rough craggy rocks just beyond the pebbles and grass. The only respite from the heat would be in the water. Beach clubs like Archeolido Egnazia are all shut up now, the tourists having returned to their everyday lives.

The water hasn’t turned cold yet. It’s warm enough to swim, which I do. I don’t jump from the rocky cliffs though. It’s a popular sport, the local boys always daring each other to go higher.

What once was a flourishing port town is slowly being reclaimed by the sea. Every wave carves a bit more away. There’s no stopping it, no prevention. The act of taking the photo is a sort of defiance. A rejection of it. I recognize there’s no stopping time, I even take a strange comfort in knowing this. But it doesn’t stop me from wanting to press pause. I point and shoot, and in my hand develops an image of ruins and the sea—or the curving paths in an ancient town, or a sunrise over the Forum. Mine forever.