Features

Five Years of MCD

2022 marks five years of MCD books. We’re mostly busy working on the next five years, but we asked our authors, our current editorial crew, and a few former MCD staffers to write up a few words about an MCD book they did not write.

The authors got to choose whatever book they wanted to write about in a highly disorganized process; sometimes another writer had beaten them to the punch, but mostly everyone got their first choice; sometimes we made a suggestion if they were having trouble choosing. (Trouble choosing? Not writers!) And the editors, who are not allowed to have favorites, mostly chose to write about their first MCD books (in one case, the first MCD book). We don’t really know how the former staffers chose; we don’t really talk to them or ever think about them (traitors).

The authors got to choose whatever book they wanted to write about in a highly disorganized process; sometimes another writer had beaten them to the punch, but mostly everyone got their first choice; sometimes we made a suggestion if they were having trouble choosing. (Trouble choosing? Not writers!) And the editors, who are not allowed to have favorites, mostly chose to write about their first MCD books (in one case, the first MCD book). We don’t really know how the former staffers chose; we don’t really talk to them or ever think about them (traitors).

As mentioned elsewhere, MCD does aspire to be some kind of weird community—of writers, of readers, all of us. We also hope that the books are in some kind of productive conversation with one another. We know it’s not programmatic or cleanly delineated, and we like it that way—but we do think the books make sense together, that it gradually becomes clear what an MCD book is (at least until the next crazy idea we have—and don’t worry, we’ve got some coming…there’s some good stuff to announce!). Anyhow, this seemed like the best way to show those conversations between the books, one author speaking to another’s ambitions and accomplishments.

The posts unfurl here in reverse chronological order—so the newest is on top, the first is on the bottom. Maybe we should have done it the other way? Well, if you want to read it like that, you can figure it out. We’ll be posting a new piece at least once a week at least until its clear that fall is here and it’s time to shut up about our fifth birthday. Time for kindergarten!

OCTOBER 14, 2022: The Doloriad by Missouri Williams

Post by Fernando A. Flores, author of Valleyesque

It is Friday! The time has come again for another entry in our Authors on Authors series to celebrate the 5th Anniversary of MCD. And this week, all we’ll say is, prepare yourselves. We’re getting trippy and fragrant with Fernando A. Flores, on Missouri William’s The Doloriad. Need we say more? Here’s Fernando:

Back in my barista days there was a coffee shop I worked that rapidly developed a rat infestation. I opened five days a week with another barista, along with one of the cooks, and some mornings we’d find individual traps with more than five baby rats that never made it to the cheese. It takes about 4 days after being born that baby rats can reproduce. Babies making babies, we’d say, clean up the rat shit and carcasses, throw away the traps, then go about our morning shift. A few times rats would die in mysterious places and you’d hope the smell of coffee and tacos would be enough to overtake the miasma of the rot of death and stink of vermin shit. One of these mornings, during a rare calm moment, a customer walked in, and by the look on their face my coworker and I knew they’d smelled this godawful smell. When they got to the counter, they took a moment to find the words, then said, “Smells like…Gummo in here.”

Like Proust dunking the infamous madeleine, the smell of a rotting rat carcass conjured up the memory of this late 90s, divisive, disturbing Harmony Korine picture. Perhaps leaving a residual smell is not something literature or art aspires to accomplish, but since reading Missouri Williams’s savage and brilliant debut novel The Doloriad I keep looking back on this particular incident, asking, of all things, what kind of smell this novel has left with me. I’m wondering if I’ll enter a room one day, or turn an unexpected corner somewhere, encounter something peculiar, to say the least, and immediately think: *it smells like The Doloriad in here. *

One of the many things I find exceptional about The Doloriad is that it feels like it wasn’t so much written, but dripped from the corner of a ceiling, slowly gathering in a puddle over time. When characters like the Matriarch, Jakub, or Dolores, come to mind, they feel like characters you see in found footage of a chaotic speculative project that never quiet came to be. The magic here, however, is not that it’s cinema, nor that it dripped from any ceiling, but that it came from Missouri Williams’s unflinching imagination.

The Cut says your Faulkner-loving dad would probably love The Doloriad, which is like saying your James Taylor-loving dad would probably love Blanky Bonkers & the Sniff-Snüff Arkestra—but you know what, yes—get The Doloriad for your Faulkner-loving dad. It’s the very least you could do for him.

OCTOBER 7, 2022: The Boatman’s Daughter by Andy Davidson

Post by Rachel Eve Moulton, author of Tinfoil Butterfly

Friday is here again! Can you believe it? Scary how fast time flies. Speaking of scary, this week we creep ever-closer into spooky season, the perfect time to grab the most hair-raising book you can find and get weird. And who better than this next pair to kick things off? Rachel Eve Moulton, author of Tinfoil Butterfly writes about The Boatman’s Daughter by Andy Davidson. And it’s only fitting that next week, Andy’s new novel, The Hollow Kind comes out! Another epic horror novel, certain to haunt and delight. But first, here’s Rachel on The Boatman’s Daughter:

I was among the lucky who got a hold of an advanced copy of Andy Davidson’s swamp-filled, bayou of a book, The Boatman’s Daughter. It was hard to resist, with that gorgeous and creepy red cover. I was immediately whisked into a world that was both entirely foreign and ridiculously enthralling. Part crime novel—think the raw emotion of Tana French—part horror—think the breathing mass of The Overlook in Stephen King’s The Shining—and part fantastical family drama—think Geek Love by Katherine Dunn, Andy’s novel was all these things and more. Unlike with Dunn, we don’t get a whole fish boy, but we sure do get some excellently scaly skin and webbed fingers. Magic potions sprinkled here and there. A severed head—was there only just the one? Bodies that dangle above us in a bottomless swamp of dreams. What astonishes me most about Davidson’s work—as with the other authors listed above—is his ability to take such a small patch of land (and water) and make it into an entire mystical universe.

From the first page, you feel like you are wading into Arkansas. The heat and itch of it is real and amidst all the water and roots and thickening canopies of trees is my favorite character, a young girl named Miranda Crabtree. (In close second to Miranda as my favorite character is the indomitable blue Igloo cooler that threatens to undo her.) It’s incredible, really. Davidson writes about a space with witches and dwarves and a devil-filled preachers. Real-life Grimm fairy tales, and yet he writes so clearly about place, about community, and about generational trauma that I don’t question the fantasy of it all. It is too real. Too full and felt.

This world, in which young women transport drugs for criminals and witches live slyly among the rest, is at its core a place struck by poverty where residents do their best to protect their own and survive. Who among us doesn’t know some version of this dark place? This home that both birthed us and now threatens to eat us? With my own work, I become obsessed with a location—the Badlands or Kelleys Island,—and I imagine the who might occupy this space in the same way that space has come to occupy me. I feel this same obsession in Davidson’s work. Miranda is brought to life in this place he calls Arkansas. Her tragedies. Her hopes. Her world made small by the humidity of it all.

It grew into me as I read—Miranda reaching her roots into the muscle of my heart until her presence was as thick and real and tangled as the Kudzu. Her witchy world took no more than a chapter to feel real to me. The Boatman’s Daughter made me think more deeply about what shape community takes in our lives. Having grown up in a small town myself, I think of it as a precious place. A place where I was seen and heard. A place where I was known. With one twist, however, such places can also keep us locked in, locked down. They act as a prison in ways that we may not recognize for years. Your own world can becomes so twisted and hectic and dark that you can’t see anything beyond it.

The magic of Davidson’s work is that it stays with the reader—quite thickly, as a place I’ve visited. I’ve sat in Miranda’s boat. Seen Arkansas through the limits and nuances of her vision. It’s a place that has become mine, waking in the dark to dreams of Arkansas, a place I’ve been and not simply read about.

SEPTEMBER 30, 2022: Ghosts of the Tsunami by Richard Lloyd Parry

Post by Robin Sloan, author of Sourdough

Another Friday is here! Which means we have a new entry in our Authors on Authors series celebrating 5 years of MCD. This week, Robin Sloan, author of several books at MCD, including new upcoming editions of Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore and Sourdough, writes about one of our most darkly inspirational non-fiction titles, Ghosts of the Tsunami by Richard Lloyd Parry, which moved Robin to tears, quite understandably so. Here’s Robin:

Ghosts of the Tsunami is a chronicle and investigation of the 2011 tsunami in Japan, with a patient gaze that attends with care both to the experience of the wave itself and the aftermath. The crushing event at the core is the disaster at a rural elementary school. I won’t say more about it here; the point of a book like this is, you need a book like this to talk about it.

In these pages, Richard Lloyd Parry demonstrates what “reportage” is, or can be. Maybe that’s a fussy word; for me, it has always seemed to indicate something particular, not quite “journalism” of the kind we get in a daily newspaper, and not “history”, either. I think reportage combines, almost uniquely, the personal with the panoramic. Richard Lloyd Parry is here in these pages, but he is never their subject. The balance is beautifully done. You could go to school on it.

If this were the same book without the ghosts — a book, therefore, with a different title — it would still be a stunning piece of work. But it is the ghosts that spin it into another dimension. Because there ARE ghosts here; real ones; possessions and visitations; and Richard Lloyd Parry’s achievement is that he does not rationalize them away into psychiatric or material phenomena; neither does he indulge them, or make a case for their cosmology. Instead, he simply: reports. He tells us what people told him about what they saw and experienced. These are not credulous naifs; they are people, canny and skeptical.

They are also sometimes haunted.

Reading this book, it seemed to me like it must have required great courage to take this approach. Maybe I’m wrong; maybe it was natural, even the only possibility. Or maybe that’s just reportage: the discipline to say, this is what I heard, this is what I saw.

So, that’s the sober reaction to Ghosts of the Tsunami. There is another.

This is the book that caved me in, sitting in an economy seat on a flight that’s now forgotten, except for this. You know it, I think: the crumple. The body’s reaction to events that knock the supports out from underneath the heart, and also, apparently, the face, so the whole apparatus falls inward; a tent collapsing; a submarine below its depth, crushed.

It was perhaps the ugliest crying I have ever done in public.

The underlying events of this book deserve tears and more. They would not have received them from me if they had not been captured with such clarity and courage by Richard Lloyd Parry. This is what reportage can do, why it’s essential. Ghosts of Tsunami sets the standard.

SEPTEMBER 23, 2022: The Death of My Father the Pope by Obed Silva

Post by Héctor Tobar, author of The Barbarian Nurseries

In our ongoing series celebrating MCD’s 5th Anniversary, we’re back with the follow-up to last week’s post, a double-feature of sorts between two incredible authors writing about the contemporary Latino experience in the US. Last week, Obed Silva wrote about Héctor Tobar’s novel, The Barbarian Nurseries and this week, we’re sharing Héctor’s reflections on Obed’s memoir, The Death of My Father the Pope. Here, in excerpt from the new foreword to the paperback edition of The Death of My Father the Pope, Héctor writes about the power of the stories and experiences recounted in this memoir, and participating in the festivities of Obed’s book launch party. You can read the text in full inThe Death of My Father the Pope out this December from MCD. Here’s Héctor:

When immigrant families produce published writers, those writers are revered, because they are a symbol of the resolve and intelligence of the people who raised them. The working people in those families sense a truth long stated by philosophers and scientists: that mastery of language is the defining element of being human. With words we tell stories, we pray, we curse. Our words express our empathy, our cruelty, our wisdom; they capture the beauty and the ugliness in our lives. We whisper those words, or shout them, or scribble them in notebooks or in poems to our lovers. When you grow up, as Obed Silva did, with stigmas of caste, race, and class attached to your person, the mastery of language elevates you. You read the stories that appear in the bound pages of a book, and you write your own stories, and you feel that these acts are essential expressions of your humanity.

Obed Silva is a Mexican immigrant who was raised by a single mother; she appears very briefly in the beginning of this book, where she offers the words of wisdom that set Obed off on his journey. And then she returns again in its final passages, where she appears in scenes that change the way we understand the entire story. Up to that point, Silva’s memoir has focused primarily on his relationship with his father. It’s a story about two men, father and son, struggling to hold on to their sense of themselves as decent human beings, even as circumstance and self-loathing cause them to slowly ruin themselves with drink. But the foundation of this book, its hidden scaffolding, is a mother’ love.

Obed’s journey to becoming an author is an improbable one. There is a hint of his past life in the inked skin showing under the collars of his shirts. His countenance, with its deep brown hue and shaved head, is one that causes a certain kind of American to recoil in fear, even though his full lips more often than not are formed into a broad smile. Cholo, they think. Gang member. He was in a gang, in fact, in another life, in the final decades of the twentieth century. But today he’s a college professor, and on the days he teaches he wears a tie and pressed dress shirts, fresh from the dry cleaners. Underneath these shirts, his tattoos honor the novelists Victor Hugo and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Those old masters are important to Obed because their books tell stories with powerful echoes in his own life; epic tales about inequality, degradation, and redemption. Stories about the forces of order trying to hunt down and crush humble men and women. Stories about the demons that men carry within them, and how those demons degrade them, and how they wrestle with those demons.

Obed’s memoir is a book that brings together great erudition—a love and knowledge of literature obtained through much sacrifice and hard work—with a willingness to face the malice and the dysfunction inside and around him. There is a natural tendency among Latino writers to treat their works as if they were a public statement of the worthiness of an entire culture. We feel the xenophobes hovering over us, and we see our books and our stories and even our poems as if they were arguments in the national debate over immigration. Put another way, we feel the need to protect our people from the judgments of outsiders. Obed Silva realizes that to do so in his own work would be to deprive his art of its greatest truths. His book is a story about the pain and the sense of grievance and smallness that define masculinity among a conquered and exploited people. Obed’s father can be warm and loving to his son and the women in his life at one moment; and then demean and strike them the next. Near the end of this book, Obed himself confesses to “the worst thing I’ve ever done in my life,” an act of cruelty he committed when he was a mere thirteen years old. The candor and courage of this work of art, and its spirit of intellectual and moral questioning, are its great achievement. Time and again, Obed joyfully and incisively deconstructs the “toxic masculinity” (a phrase he thankfully never uses) around him, invoking Chaucer and others to reveal the secret smallness inside the male bully.

I saw Obed’s joy and fearlessness on display at his very first post-publication reading, a book launch at an Orange County restaurant. He and his friends and family rented out the space for a night and filled it with more than a hundred people. Obed held court from a small platform, his friends having lifted his wheelchair up there. There was much cheering, shouting, and laughter—it may have been the most boisterous book launch in American history. Some of Obed’s old friends from his gang life (guys in their forties, like him) were there, along with their families. When Obed mentioned that some of these “homeboys” had been in jail, as he had, one of the homies’ wives covered her young son’s ears. Obed introduced the audience to many of his uncles and cousins, and even the first girl he’d kissed when they were eight years old. The college professor who testified on his behalf in immigration court was there too, as was his Cuban American lawyer, who had once helped rescue Obed from what might have been a decades-long prison sentence. And, of course, Obed’s mother, Marcela, was there, beaming from start to finish. Obed read several passages, and ended with one where he describes how his own drinking sabotaged his life and happiness again and again, even in the years after his father’s death from an alcohol-induced illness. Without any fear in his reading voice, Obed bared himself in front of his loved ones, his homies, his blood relatives, and his mother. “I am two people,” he began. It was the bravest thing I’ve ever seen an author do.

–

The Death of My Father the Pope is out in paperback December 6, 2022

SEPTEMBER 16, 2022: The Barbarian Nurseries by Héctor Tobar

Post by Obed Silva, author of The Death of My Father the Pope

It’s time again for another entry in our ongoing Authors on Authors series. This week, we’re gearing up for an incredible pair of back to back posts by authors on one another’s books. The first is Obed Silva, author of The Death of My Father the Pope, whose reflection on Héctor Tobar’s The Barbarian Nurseries begins with a meme. Here’s Obed:

He’s a Mexican boy around eleven, the same age as the eldest of the two brothers in The Barbarian Nurseries by Héctor Tobar. However, while the brothers in the novel live a privileged life in a gated community in Orange County, California, this boy lives in a seemingly different world. In the meme, he’s sitting on a battered bike with one foot on the rocky ground and the other on one of the bike’s pedals. He has one hand gripped onto the handlebars and one wrapped around a frosty plastic cup of agua fresca. His hair is shortly cropped, his skin a reddish brown extra dark around the neck, face and forearms from the sun. His eyes sternly stare at the person snapping his picture. Displayed prominently in the image is the cardboard sign zip-tied to the handlebars that reads SE HACEN MANDADOS (I MAKE DELIVERIES). Above the picture, the creator of the meme wrote “Se muere de hambre el que quiere” (He who wants to, dies of hunger). This meme has over 10,000 likes on Instagram.

The Barbarian Nurseries can be read as a cautionary tale to parents of adolescent children. For although Brandon and Keenan will not die of hunger, their parents, by overindulging them, are setting them up for failure. The boys may have all of the commodities they need and more in their room of “las mil maravillas,” including an abundance of books and technological devices to further their education and keep them pacified, but what they lack in their soft bunker is ganas—grit—a key human trait required for one’s survival in a world that is becoming increasingly difficult to navigate. It is only a matter of time before their tech gadgets kill their books and become appendages to their bodies, eventually taking over their thoughts and controlling their lives, and sooner than later, the brothers will become like the “thoroughly medicated boys next door,” either too hyper, too slow, too anxious, or too damn depressed. Much like their parents, they will not know how to communicate and create healthy relationships. Even worse, without ganas, and only the screens on their phones and other gadgets to direct their lives, when a real-life problem presents itself, the brothers will not have the necessary tools to address it. Like their brittle parents, instead of confronting the problem head on, they will run away from it and in doing so create a much bigger one.

The Mexican boy from the meme, however, will live a content life, even without luxuries and wealth. He’ll grow up to be both survivor and provider. Like Araceli, the hero of the novel, he will take action when an unforeseen problem arises. Therefore, the best thing that happens to Brandon and Keenan is Araceli taking them out of their room of “las mil maravillas” and on their adventure across Orange County and Los Angeles. Through it, they are able to experience hardship and in the process gain a little bit of ganas.

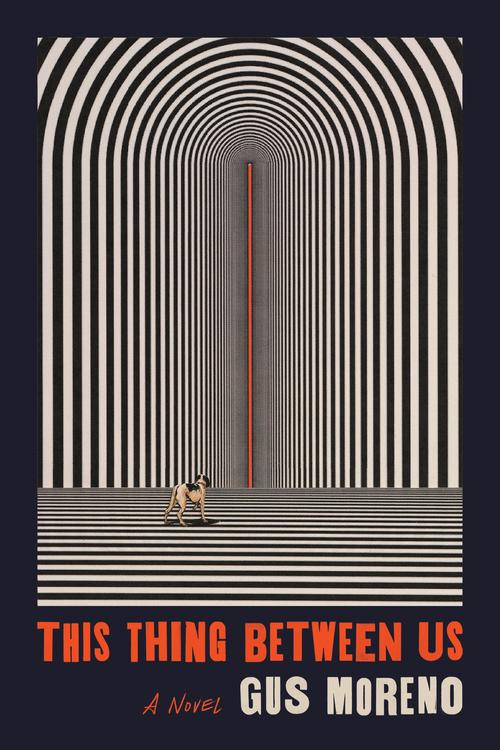

SEPTEMBER 9, 2022: This Thing Between Us by Gus Moreno

Post by Jeff VanderMeer, author of Hummingbird Salamander

Itza, what day is it today? Oh, Friday? And it’s almost fall, aka peak horror season? Then what better way to get spooky than with another Authors on Authors post to celebrate MCD’s fifth anniversary? This week, Jeff VanderMeer shared his thoughts with us on Gus Moreno’s This Thing Between Us, a moving and chilling exploration of grief, with a smart-device named Itza at its dark center. Here’s Jeff:

One striking thing about Gus Moreno’s wonderful (horrifying) and poignant (horrifying) debut novel This Thing Between Us might just be how the MCD cover perfectly renders both the subtlety and intensity of the story. This kind of synergy strikes me as so important to how a reader enters a novel. We are thrust into a kind of hall of mirrors that is also a maze, with the tantalizing yet also slightly terror-inducing promise of some way through in red in the distance. Is this passage from life to death or a journey far more wide-ranging and original? The image also evokes, for me, the description of the Itza, an Alexa-like device with perhaps infernal underpinnings. (There’s even a kind of nod to the Gothic genre in how this maze/mirror hall also resembles the arches of a sinister cathedral or church.)

Which is all to say that Moreno’s signature achievement in This Thing Between Us is to provoke from MCD’s art and design departments a need for a unifying image that is also extremely complex. We are led into the novel by the voice of the narrator, Thiago, talking about his dead wife (and talking to his dead wife). This alone would be enough to propel any novel forward, given Moreno’s profound insights into grief and into mourning and relationships. Yet we are also captured by the off-kilter nature of the technology, intertwined with this rhapsody on grief, and we stick around because that’s only the opening gambit of a novel both psychological and terrifyingly real. Itza deserves some real respect given that until recently the horror genre worked, even with contemporary settings, by having cell phones that can’t get reception, wireless dropping out, and similar ways of negating modern technology. Instead, Moreno leans into that technology to create some genuinely sinister moments, all while never losing focus on the emotional heart of the novel.

But, yes, just like on the cover, there is a pivotal dog in Moreno’s novel, and a change of setting from the urban to the wilderness, as our narrator attempts through that remoteness from familiarity to handle his grief. And it’s in that place, with that dog, that This Thing Between Us gets truly weird, the novel transforming from the thing it was to the thing it is. In doing so, Moreno conducts a kind of masterclass in different kinds of horror and different effects of these approaches, all integrated into the central premise.

To say more is to give away too much, but I appreciated how This Thing Between Us throws caution to the wind and just simply goes for it. Who knows what waits for us in the distance, but we know by the time we reach it, we will have been transformed.

SEPTEMBER 2, 2022: High School by Tegan and Sara

Post by Gus Moreno, author of This Thing Between Us

It’s finally Friday, and that means we have another Authors on Authors post in celebration of MCD’s 5th Anniversary! This week, we have Gus Moreno, the brilliant mind behind This Thing Between Us discussing the subtle intricacies of Tegan and Sara’s music, as well as the complicated observations they make about adolescence in their memoir, High School. Here’s Gus:

The first time I heard Tegan and Sara’s music, I was working at the Gap. This was in 2008, at the peak of the Great Recession, and it wasn’t even a part-time job—it was seasonal. Meaning I had to bust my ass and show how valuable of an employee I was just so they didn’t let me go once the holidays were over. I hated everything about the job: the money, the customers, the other employees who thought they were God’s gift to retail, and I hated listening to the same music playing through the store’s speakers day after day, week after week.

I don’t remember the first time I heard “Where Does the Good Go,” by Tegan and Sara. Music sort of melted into a white noise during my shifts. But at some point the song started to stand out to me. I noticed it each time it played, and after a while it became the only thing at work I looked forward to, the chance that I would get to hear this song in the middle of folding clothes or marking down sale items. In a place so concerned with surface details, the song was a salve of reality. It felt so honest. Every time I heard it I was jolted out of my lull and brought back to life.

It’s no surprise then that High School, Tegan and Sara’s memoir, is just as vulnerable and sincere as their music. But it’s a vulnerability that borders on transgression, a sincerity that engulfs you in heartbreak and disappointment. Tegan and Sara alternate the writing duties, switching off chapter by chapter, and what they detail are the most excruciating parts of being a teenager: the cynicism, the rage, the confusion, the mania. It’s about coming out. It’s about the birth of an indie duo. And it’s also about navigating your own feelings, and the struggle to become who you are.

Don’t open this book if you’re looking for the story beats of every rock n’ roll biography. Yeah there’s drugs and sex and blood in these pages, but the same pages are also filled with the in-between moments that make up the majority of adolescence: talking on the phone, the urge to disappear in front of the popular kids, fighting with your sibling, waiting for your crush to make the first move, thinking this break-up will be the most devastating thing in your life.

I mean God did this take me back. The more I read, the more I was there with Tegan and Sara, packed into a friend’s car for a night out, when absolutely anything could happen, pretending we were all made of Teflon only to fall apart at the slightest thing. The sound of a house party peaking before it descends into chaos, the static electricity that tickles your lips before kissing someone new, the urge to express yourself without realizing the artistic course you were setting yourself on, it’s all there. Written in the same concise language as their lyrics. Which means this book, it cuts deep.

AUGUST 26, 2022: In Our Mad and Furious City by Guy Gunaratne

Post by Danny Vazquez, MCD Alum

Another Friday is upon us in the mad and furious celebration of MCD’s 5th Anniversary. We’re back with another post from a past MCD-er, Danny Vazquez, to discuss his very first in-house acquisition, Guy Gunaratne’s Booker Longlisted novel In Our Mad and Furious City. Here’s Danny:

From the very first sentence of Guy Gunaratne’s In Our Mad and Furious City, I knew there was no one at FSG, maybe no one stateside, who would see in the novel what I saw. Written largely in the patois common in London’s council estates, I called it “the first proper grime novel”—a misstep, sure. Grime still hadn’t quite taken off here yet (it still, unfortunately, hasn’t). The slang and the slums of Northwest London were and remain wholly foreign to most American readers. It might have been wiser to lean into what Parul Seghal called its “incubated in a library” quality. This was a book with a sense of history. It’s a book concerned with the ways in which we are radicalized and the traumas which, over generations, inform our lives. I love this book. I think Guy is a genius. I only wish Americans had better taste in music. —Danny Vazquez, Senior Editor, Astra House (formerly of MCD x FSG)

AUGUST 19, 2022: LaserWriter II by Tamara Shopsin

Post by Olivia Kan-Sperling, MCD Alum

Plug yourself in, dust off your monitors, unknot all those cables under your desk, because it’s Friday, and we’re sharing another post in our series celebrating MCD’s 5th Anniversary. For the first time, we have a post from a past MCD-er, Olivia Kan-Sperling. You may know her from The Paris Review or from her new book, Island Time, either way, Olivia is back with her thoughts on one of our titles that’s stayed with her even past her days here at MCD, LaserWriter II by Tamara Shopsin. (If you haven’t already, be sure to check out Tamara’s photo essay about Robin Sloan’s Sourdough) Here’s Olivia:

I started as an editorial assistant at MCD shortly after college, hoping to combine an embarrassingly eclectic range of academic interests that included computer programming and just straight-up “language.” In the intervening months I’d done a couple of remote jobs involving what I’d aspirationally call avant-garde website design, though it was actually far humbler in its execution: picture a site where you have to click jpegs of pigeons in order to reveal a “digital care package” of book pdfs disseminated by several small publishers. Anyways, I thought such whimsical forms of “thinking outside the box” were behind me. Many cover letters I’d written in the hopes of “intersecting” x and y ended up allowing me to do neither—but, with MCD, I was lucky!

One of the first manuscripts I would read was Laserwriter II, Tamara Shopsin’s “coming-of-age tale set in the legendary 90s indie NYC Mac repair shop TekServe—a voyage back in time to when the internet was new, when New York City was gritty, and when Apple made off-beat computers for weirdos.” I copy/paste the jacket copy in the spirit of the book, which is about reusing and recycling parts to make new wholes, and because I helped write it, so I think it’s a good description. I couldn’t have asked for a more perfect “intersection.” Not just because it’s a novel about computers, but because Shopsin does—in simple, straight-up language—what I found genuinely exciting about the tech world: come up with something new, but user-friendly. “Push boundaries,” “think different.” There were long interludes consisting purely of dialogue between printer parts. There were shorter, but still surprisingly long, descriptions of surreally opulent brunch spreads. There was an office, and interesting people in it. There was an epilogue pleading with you to back up your data. And there were beautiful illustrations—Shopsin’s micro-level descriptions of computer parts were matched by her minute attention to the material qualities of her book. I don’t think many publishers would have let an author engage so deeply in the design process (Shopsin did the cover herself!), which is sad. A physical book should be an exquisite, intentional, expressive object—otherwise you could just get a Kindle—and every MCD book is.

MCD has published other novels involving tech (This Thing Between Us), and nonfiction about Silicon Valley (Uncanny Valley), and even an augmented-reality-supplemented graphic novel (Book of Darryl). But Laserwriter II is extra-special to me because it shows us the box-pushing narrative affordances of our most modest technology: writing. The conservative commitments to realism, conventional prose, and single-medium stories held throughout much of literary publishing are so disappointing to me; the constipated forms of experimentation that sometimes crop up in alternative spaces are, often, equally boring. I think it’s okay for good books to be difficult, but the beauty of Laserwriter II is that it’s not. It reminds me of the 2008 iPod Nano Chromatic: small and streamlined, cutting-edge but cute, just sparkling and brilliant and surprising and simple.

August 12, 2022: My Parents by Aleksandar Hemon

Post by Nathaniel Rich, author of losing Earth

Another Friday is upon us and we have another entry in our MCD Authors on Authors series to celebrate our fifth anniversary. Last week, you read about Nathaniel Rich’s Losing Earth, this week, Rich shares his thoughts on our resident genius (one of them, at least), Aleksandar Hemon. Hemon’s memoir My Parents and its accompanying flip-side memoir, This Does Not Belong to You are two sides of the same physical book, a work that asks you to look at every story from a new and different perspective…literally.

My Parents is an elegy made more powerful by the fact that it was published while its octogenarian subjects were still alive. That takes some hrabost (that’s Bosnian for guts). Reading the memoir you sense Tata and Mama peering over your shoulder, interjecting with cavils, murmurs of disapproval, and tears of profound emotion, perhaps accompanied by impassioned song, something to the tune of “Ivanku T Y Ivanku,” say, or “Rospriathaite Hloptsy Konyi.”

In the kind of eccentric publishing feat at which MCD excels, My Parents is paired in the same book with a second, complementary memoir, This Does Not Belong to You, the two volumes front-to-back and upside-down from each other. No matter whether you begin reading from the left side or the right you always end up in the middle, which is a decent metaphor for the art of memoir. A great memoir doesn’t terminate so much as plunge the reader deeper into the lives of its subjects. Whether you begin a life at birth or death you end up in the heart of it all.

Heart, the Hemons have. They are a joy to be around, even when they’re complaining, or especially when they’re complaining, as they do about portion sizes at fancy restaurants, buckwheat honey, and the chidings of doctors to avoid red meat. (“It’s not red, the bacon,” says Tata, defending himself to his flummoxed son. “It’s all white.”) Most of all they direct their pique at the shortcomings of life in Hamilton, Ontario, where they fled after the war in Bosnia, having taken the last train out of Sarajevo before it was besieged. Drab Hamilton cannot possibly live up to Sarajevo, or the Hemons’ ancestral Ukraine, especially since with each year abroad the majesty of these native lands continues to flower in their imaginations. Hemon writes that the story of his family is “rooted in removal.” But the corollary is also true: their lives also oriented by the desire to restore what has been lost. Memories are unreliable, however, so such restorations are doomed to fall short.

Undaunted, the Hemons dedicate their lives to the struggle. Hemon’s mother compulsively rewrites the past in her mind, lamenting lost opportunities and imagining how “it could have all been different.” His father throws himself into hobbies with enviable severity. He seeks out lamb heads for boiling from supermarket butchers, sings traditional Ukrainian anthems in a family choir, and hatches a plan to smoke meat in a jerry-rigged smoker fashioned from two discarded refrigerators in the basement of his apartment complex. Most of all he dedicates himself to his bees.

Hemon comes from a long line of beekeepers. During the war, his father’s apiary—“his soul”—was destroyed: a honey thief kicked the hives into the snow, sentencing the swarms to a frozen death. Heartbroken, Tata sets out to recreate his bee kingdom in Hamilton. He transplants hives to the roof of his apartment building and later, after moving to a house, creates an apian paradise in a nearby forest clearing. In Hemon’s loving portrait of his father’s obsession we can see the origin of his own. Tata, Hemon writes, had created “a domain in which he can practice agency with dignity and some form of sovereignty. What beekeeping is to him, literature is to me.” The story of Hemon’s parents, when held up to a mirror, reveals, in reverse image, the development of a writer’s conscience.

As Tata writes on the labels of the honey jars he sells to his friends and family members, “the natural form of honey is a crystal.” My Parents is a crystal.

August 5, 2022: Losing Earth by Nathaniel Rich

Post by Alan Heathcock, author of 40

The earth apparently is spinning faster and faster, bringing up to yet another Friday, a bit sooner than expected, and another post in our Authors on Authors series. The faster we spin, the faster we lose what we still have on this planet. Scary, right? It’s fitting that the author of the newest MCD title, 40 (published earlier this week) is up this week to talk all things end-of-the-world, and Nathaniel Rich’s Losing Earth. Here’s Alan Heathcock on the book, the Bible, and believing we can make it out of this alive:

Nathaniel Rich’s Losing Earth begins with an epigraph from the book of Proverbs in the Christian Bible. The verses condemn the fools of the world for rejecting knowledge, and a divine personification of Wisdom that scolds the fools because, “I stretched out my hands and no one paid attention; and you neglected my counsel and did not want my reproof.” Wisdom says she will mock the fools when their dread comes like a storm.

When our dread does come like a storm. Storms, indeed. Storms both figurative and literal plague this era of increasingly dramatic climate events; hurricanes, floods, wildfires and quakes and droughts. It may seem strange that a book largely about the proof, or denial, of science opens with religion, and yet it seems appropriate when chronicling the scale of the existential dangers of climate change.

Though the wending machinations of the betrayal of climate-science are complex, the thesis of the book is relatively straight-forward—between 1979, when we were on the verge of a global climate treaty, and 1989, when the Reagan-era philosophy of deregulation became the full blown climate-denial we’ve witnessed ever since, we had a chance to take significant and lasting action. Nathaniel Rich is also a novelist, and Losing Earth reads like tragedy, as the likes of Rafe Pomerance and James Hill navigate politicians and industry lobbyists to sound the alarm on the ever increasing dangers of our warming climate. It’s a fascinating and gripping tale, and one that left me bereft and furious.

One morning, after reading Losing Earth, I needed a break. It was too much. My mind spinning, I took a long hike out through the woods near Boise, Idaho. It was a sunny day with a pleasant breeze. I sat beside a lake and watched goslings swim behind their mother, but my thoughts were only on our demise. I needed to talk out what I was struggling to process, and texted a friend to meet me for lunch. At lunch, I did my best to paraphrase what I’d been reading, punctuating my outrage, expressing my fear and anger. My friend, who is a long-time environmental activist, looked concerned. Finally, she said, “It’s such a nice day out today. Why don’t we change the subject?”

I don’t fault my friend, because I, too, wanted to not think about a future made unstable by our ever-shifting climate. But I can’t stop thinking about it, and carry Rich’s findings with me everywhere I go. The battle is not just that the industry lobbyists have been incredibly effective, and only 42% of Republicans know that most scientists believe global warming is occurring, but that even those of us who already believe in the science don’t understand the insidious history of denial we’re up against. I’m hopeful by nature, and what makes Losing Earth an important book for those who hope for change is that it arms us with the power of truth. Back in 1979, we saw the looming dangers. Now the proverbial storm is here, and with every tenth of a degree the global temperature rises the closer we come to biblical calamity.

As alluded to through the epigraph chosen by Nathaniel Rich in this amazing and important testament of reportage, we are living as if in a story from the Bible. We are indeed Losing Earth. If there is a god may god help us hear the cries of Wisdom and, despite our dread, find the will to reject the fools and save ourselves.

JULY 29, 2022: Sourdough by Robin Sloan

Post by Tamara Shopsin, author of LaserWriter II

It’s friday… you know what that means! Once again, we are sharing a new entry in our Authors on Authors series, this time, with a new, special ingredient. Several, actually. To talk about Robin Sloan’s tasty and techy novel, Sourdough, Tamara Shopsin (author of LaserWriter II) gives us a story in images, a found photo essay from the images using, you guessed it, her iPhoto library. Honestly, it’s everything you didn’t know you needed. You’re very welcome:

Sourdough by Robin Sloan reviewed by Tamara Shopsin (using her iphoto library)

This photo is a little dramatic, but it gets at an essential element of Sourdough: the San Francisco food scene.

In the book a sourdough starter needs to be fed to live, but it is more complicated than it seems, much like this mug.

You wouldn’t think the desires of a clump of yeast could propel you through a book, but they do.

I feel like I should also mention the robotic arm.

Read Sourdough.

Tamara Shopsin is the author of Laserwriter ii.

JULY 22, 2022: Sharks in the Time of Saviors by Kawai Strong Washburn

Post by Rosecrans Baldwin, author of Everything Now

Cue the cello overture because it’s time to talk sharks! Last week, we shared Kawai Strong Washburn’s entry in our Authors on Authors series, celebrating the books of MCD for our fifth anniversary. This week, Rosecrans Baldwin, author of Everything Now writes about Kawai’s novel, Sharks in the Time of Saviors, an expansive debut about myths and miracles, and one of President Obama’s favorite books of 2020! We love to see it. Here’s Rosecrans:

I didn’t see this novel coming at all. I’d never heard of the author. My experience of Hawai’i was a single visit, to the northside of Kauai, and my knowledge of its literature was poor to none. But I loved the book’s cover and gave it a few pages – then just gave over fully to it and finished it a few days later, and started pressing it on everyone I know.

The story in Sharks is thrillingly felt, and told with great style. The Flores family, struggling in non-tourist Hawai’i, one day watches their son Noa, one of three kids, be rescued by sharks, which puts him on the evening news. Then he seems to develop healing powers, which begins to help to pay the family’s bills. From there, we’re in and out jobs and kitchens and streets and fights, the conflicts that tear them apart and the love and history that still bind them. The storytelling is light, sophisticated, never gilded, always sharp, also full of gorgeous nature writing – and how nice for a book about Hawai’i to focus on the islands’ interior lushness, their wet mountainous greenness, and not the beach.

There are storylines and moments that transcend time and place. Miracles, gods, ancestors, old South Pacific politics. But Sharks goes most deeply for me when it’s rooted in today’s world, on and off the islands: basketball and drugs, rock climbing and sexual identity, poverty and food. Who do we belong to? Is any person more special than the next?

It’s no lie to say I don’t remember the last time I owned a copy of Sharks, I can’t stop giving them away. The Flores children are today’s children and I fell for them hard.

JULY 15, 2022: The Golden State by Lydia Kiesling

Post by Kawai Strong Washburn, author of Sharks in the Time of Saviors

It’s Friday again, which means we share a new addition to our Authors on Authors series! This week, Kawai Strong Washburn, author of Sharks in the Time of Saviors writes about Lydia Kiesling’s riveting debut novel The Golden State, parenthood, and the bewildering feeling that is being alive right now:

The fall of 2018 when Lydia Kiesling’s The Golden State came out, my wife and I were partway through the first year of our second daughter’s life, and my heart was swerving wildly between ecstasy and despair, sometimes within the span of minutes. The reason was simple, and the reason was parenthood: specifically, parenthood in the Bay Area of California, with its vicious contrasts in wealth and poverty, a strange young money rave of techno utopianism teetering on the knife’s edge of environmental and community collapse. The country was two years into a Good Ol’ Boy’s wet dream of America, with a Federal administration militarizing the borders while gleefully shredding the last vestiges of environmental and social policy.

Into that utter darkness dropped Kiesling’s book. It gave me and my wife exactly what we needed: validation of the terror, tenderness and transcendence of parenthood married to a road trip with nowhere good to go, the protagonist unable to flee the parts of herself and the world that needed to be faced most directly. We recognized the remote and unvarnished parts of California with empathetic truth (The State of Jefferson!), we loved the perfectly rendered sixteen-month-old Honey, we felt the stinging reminder of our privilege when seeing a couple struggle to navigate the bureaucratic cruelty of immigration law. And the narrator was so funny! It was like hearing a long story from a favorite friend, one with no fucks to give that will nevertheless have every mother’s back to the end.

It had been a while since I’d read a book about young motherhood, especially in which motherhood itself was not a topic being used as a proxy for some other, more established battle (whether race, welfare, or abortion). Yes, those topics intersect often with parenthood in ways that multiply disadvantage, and this needs to be discussed constantly, even in literature; but this book took a different route, with Kiesling expertly describing mostly the daily burdens of parenthood, detached from any context but its own: the horrors of even a short car ride with a toddler, the oscillations between boredom, bewilderment, self-flagellation, and, finally, joy, the failure to uphold previously strong boundaries of discipline. Not to mention the onslaught of logistical complexity in feeding, cleaning, sleeping, and supporting the development of a young child.

It worked so well for my wife and I as readers that we found ourselves quoting lines from it randomly during some of our worst days. Anyone who was listening in would’ve thought we were insane, but it made us laugh and gave us comfort. That’s not all this book does—it does plenty more—but for us, right then, it was exactly what we needed.

JULY 8, 2022: Nevada by Imogen Binnie

Post by Dan Bouk, author of Democracy’s Data

The next entry in our Authors on Authors series is by Dan Bouk, whose forthcoming book Democracy’s Data (out August 23) explores the stories hidden in US census data. It fits, in a way, with the novel he’s written about here: Nevada by Imogen Binnie, the iconic trans “road novel” that tells of these characters’ search to find meaning, and to claim space within the confines of varied structural/institutional limits imposed by this country. Maybe it’s a reach. But maybe it’s the perfect match. We’ll let you decide.

I wasn’t sure what I was in for, when I opened this book. Sean asked me to read it, maybe because I’m part of a queer household—and indeed that did make Imogen Binnie’s Nevada easy to relate to. But if I am honest, I would prefer to believe he invited me to read it because he thought I cared as much about the dignity of the folks I write about as Binnie cares about these characters.

Halfway through Nevada, Binnie gives us this line: “It’s clear that being responsible has not been a positive force in her life.” It’s describing an idea the protagonist, Maria Griffiths, is just then working out, or maybe taking for a spin.

She’s thinking about all the responsibility she had borne up to that point: a responsibility to hide, to fit in, to cram herself into the identities or check-boxes or cheap clothes that had been assigned to her and declared acceptable. She bore that responsibility to protect herself, but more so to protect those around her, from discomfort, from standing out: “When she was little, she was responsible for protecting everybody else from her own shit about her gender—responsible for making sure her parents didn’t have to have a weird kid.” This is a burden children bear, and especially trans kids. I fear that burden and those lines carry extra weight today too, as terrifying as Alabama and Texas (and possibly other states soon) threaten parents who support their trans children with imprisonment. So many weird kids, trans kids, will suffer more than before under the responsibility to suppress and repress everything, to keep their parents out of jail.

That is too much responsibility. “It has been fucking everything up.” It is heart-rending.

Maria sets out to be irresponsible. She imagines tattooing it across her knuckles, like this: (here is my artist’s reconstruction)

Nevada is ostensibly a road novel, but it has precious few road scenes. (Which is great because I don’t really like road novels.) Maria does make some forays into irresponsibility though. And she may, or may not, grow or change or evolve. Mostly she tries.

That’s one of the things I loved most about this novel—and I loved this novel: folks are really trying, just doing their best, to muddle through the muck, even though they are frequently quite terrible at it. There is so much dignity in trying and failing, and I admire so deeply how Binnie honors these characters, letting them slip up, make mistakes, and then try again.

The book reminded me of an essay by William James, who (on his good days) tried to make space for a nearly infinite variety of experiences. He answered his own question in “What Makes a Life Significant?” this way: “The solid meaning of life is always the same eternal thing,– the marriage, namely, of some unhabitual ideal, however special, with some fidelity, courage, and endurance; with some man’s or woman ‘s pains.–And, whatever or wherever life may be, there will always be the chance for that marriage to take place.”

Maria seems to conclude that irresponsibility isn’t the answer. “Obviously, that turned out to be a totally stupid theory though.” What she wants or needs, and has wanted and has needed, is to be able to change and grow, and then to keep changing and growing. The centrality of “transition” of moving from one state to another in the way that trans lives are often described or treated or legislated can make it harder to keep making new and different choices, to trying on new and evolving selves: “I think what I meant was that I need to stop feeling responsible, to everybody all the time, for presenting this consistent and static face. And I needed to get over the idea that being responsible in a relationship means being consistent and stoic and out of touch with my feelings.” Maria needed the freedom to continue to change.

Nevada is a liberatory novel, a novel that courts inconsistency while it throws some elbows to make space for a wider variety of lives. It details how communities and relationships confine, and how much we all need them in order to thrive. It is marvelous. And I’m pretty jazzed it will soon be a wiser and much more profane big sibling to my new book.

JUNE 24, 2022: Sorrowland by Rivers Solomon, and The Best Bad Things by Katrina Carrasco

Post by Nicola Griffith, author of So Lucky and Hild

We kick off the weekend by continuing our ongoing celebration of MCD’s fifth anniversary (and Pride!) with with another fab entry in our Authors on Authors series, this time diving into the weird and transformational world of Sorrowland by the author of So Lucky and Hild, Nicola Griffith. And Nicola’s surprise second book bonus, an additional take on Katrina Carrasco’s The Best Bad Things:

I’d never met Rivers, but I knew of their work (An Unkindness of Ghosts, The Deep), and was delighted when their latest book was acquired by MCD. So when Sean asked if I would read Sorrowland I agreed—even though I had no clue what it was about. Or even what genre. There again, I don’t give a flying fig for genre, as reader or writer. As a writer, genre is just the kind of vehicle you choose to cross a particular story terrain—you wouldn’t want to cross a desert on a scooter or an ocean in a Subaru—you just have manage genre-specific reader expectations. And one of the things I love about MCD is that they seem to think the same way. (Insert gleeful paean to how refreshing—for my career, life-saving—that is.)

Anyway, when I picked up Rivers’ book, I was expecting…anything. Even so, I was amazed by it. If ever you want to experience how it is to be a woman who has everything in life arrayed against you simply blow through obstacles like a gale through a spore-drift, read this book. It will give you confidence that there’s always a way to not only handle what life throws at you but find the joy.

Sorrowland is a raw, powerful, and visceral read. With Vern, Rivers Solomon has created a woman who simply side-steps her damage and level after level of difficulty―young, Black, queer, blind, alone in the woods with two newborns, and pursued by monstrous government agents―to assume her own strength. The book burns with physicality, exploring, even revelling in, nature, science, belonging, human metamorphosis, generational oppression, joy, and sheer lust for life. If Toni Morrison, M. Night Shyamalan, and Marge Piercy got together they might, if they were lucky, produce something with the unstoppable exhilaration of this novel; it is sui generis.

And that is what MCD does: finds the books that do what no other books do. It ignores the rules of genre. And hey, because this is about what makes MCD MCD, I’m going to ignore the rules, too, and write about another book that is like nothing else I’ve ever read.

Katrina Carrasco’s The Best Bad Things is a gritty, hard-drinking hymn to the lawless late 19th century when Port Townsend was the Deadwood of the Pacific Northwest. Alma is an undercover Pinkertons detective tracing an opium-smuggling network reaching from Tacoma to Vancouver BC. Or is she? Because Alma is also sometimes Jack, and Jack has an entirely different agenda.

Carrasco uses a whippy structure and flexible prose to play an unsettling shell game as Alma, dressed as Jack, sheds her impulse control along with her corsets, and the plot accelerates into an unexpected underworld of bare-knuckle fighting, opium smuggling, and genderqueer lust. Both Jack and Alma are creatures not of the head—or heart—but gut. In the streets and between the sheets they live for the thud of bone on bone, wrench of muscle, and tear of breath. Neither they nor Carrasco flinch before bold choices and the result is an absolutely jaw-dropping knife-thrust of an ending. The Best Bad Things is a bloody brawl of a book.

JUNE 8, 2022: 100 Boyfriends by Brontez Purnell

Post by Jaime Lowe, author of Breathing Fire

Our Authors on Authors series continues, kicking off Pride Month celebrating the work of the “gay punk messiah,” the one and only Brontez Purnell. For all the good, queer vibes, feels, and philosophy on life, we have a deep dive into Purnell’s 100 Boyfriends by author of Breathing Fire, Jaime Lowe:

On the front cover, a penis, a bridge, a tongue, a mountain, a wave, a heart; on the back cover, a shirtless Brontez, the author, staring down the lens, hands resting on jean pockets, but not in them. Standing there, naked as he can be and still selling copies in Barnes & Noble.

I told Sean that was the vibe I wanted in my author photo. He said Brontez would show up to marketing meetings shirtless. I said, damn, maybe I should too, making everyone uncomfortable since my shirtlessness would incite an HR meeting. I regretted making the joke, but Brontez’s nakedness is what 100 Boyfriends is about. His nakedness on display through clarified writing. The writing is so clear, so precise, not one word out of place, not one word gratuitous. Linked vignettes of scenes and portraits braided with desire and body and fluid and power, tenderness and messy raw sex, sometimes broken, sometimes orgasmic, sometimes both.

I read the book, needed to read it, devoured it really.

I was so hungry for this titillation, these extreme human interactions in a time when I was siloed, the world was siloed. Boyfriends came out in February of the first Covid winter, before the vaccine, and provided this portal to humor, to touch, to flesh, to want, to a little bit of frivolity AND THAT IT WAS OK TO BE FRIVOLOUS. Important even, life sustaining.

I needed to hear from the Brontez Purnel, the artist, his gogo dancing, his steam baths, his fucking, his loving, his cumming, his gazing, grazing, ball gagging, blind folding, petting, putting out, putting in. To read about his bodies, many bodies. All the dirty details in a swirl of love, care, feeling, numbness. Memory and sensation. All of it. Blurry but clear. Real but maybe fiction? Fiction but maybe real? It didn’t matter. It was a riotous bouquet of humor, terror, cattiness and love.

Boyfriends is a gateway drug. I watched Brontez Zoom readings, went into a deep dive — Brontez punk, Brontez dance, Brontez Instagram live, Brontez in a metallic g-string, Brontez gyrating, Brontez grinding, Brontez face tattoos, Brontez pool parties, most recently Brontez fully naked getting a buzz cut. He advertised a room for rent in his house in the Bay Area and for a second I thought maybe I should leave my life and bask in the glory of Brontez. Join the cult of Brontez.

Why was I so taken with this book, these stories, this voice, this person? This person aptly known as a “gay, punk, messiah”?

Cloaked in fiction, he seemed to also offer himself whole, seemingly unaltered, absolutely clear about who he was, how he lived and what he wanted. The book has been described as transgressive, and maybe it is in some ways, but it follows a traditional narrative structure. Each sentence, finely crafted, each story, deftly edited. Pulling you in with details and emotional resonance about his characters, about him, his world, his life, what the flap copy describes as the “unexposed queer underbelly.” The book is not really about the one hundred boyfriends, it’s about the Brontez. Whoever Brontez is, the small sliver revealed in those 177 pages is enough to know the world needs more. And also, please, maybe start that cult?

MAY 13, 2022 (Friday the 13th!): String Follow by Simon Jacobs

Post by Chris Harding Thornton, author of Pickard County Atlas

Chris Harding Thornton, author of Pickard County Atlas, decided to write about the eerie and hilarious String Follow, by Simon Jacobs. We asked Chris to describe her experience reading the book, and, well, she delivered.

Here, we are lucky enough to get an inside look at Chris’s evolving thoughts on String Follow, and what makes it such a trippy, thrilling tale.

WARNING: EXPLICIT ACCOUNTS OF DRUG ABUSE AHEAD. MCD DOES NOT ENDORSE OR CONDONE THE USE OF ANY DRUGS. NOTE: WE DON’T NOT ENDORSE IT EITHER, ESPECIALLY WHEN IT’S FUNNY.

Heya—

I had a massive allergy attack and wound up writing like 2k words, but I honed it down. Let me know if it works–if you had something else in mind, let me know, and I probably wrote it!

-c

When I try to describe String Follow (and I find myself doing it a lot), I tell people it mixes horror and (maybe) supernatural suspense as it follows a huge cast of angst-y teenagers who find kinship (and don’t) in being outcasts. But that description is way too simple for a really complex and ambitious book.

First things first, if you grew up in an underground music scene, especially one that fell under the huge umbrella of “punk rock” or that held tight to “DIY ethos”—if you know what a “zine” is—this is a must-read. If you’d laugh at someone saying, “The Misfits were more of a Hot Topic brand than a band at this point,” just go buy the book right now.

But even if you’ve lived outside those things, the prose is intoxicating and hypnotic (I’ll come back to the hypnotism), and the characters, whether they make you cringe or break your heart or both, wind up being people you feel like you know. If you really like being creeped out, this book definitely does that, too.

But String Follow is also about way larger, all-too-relevant things. Take the “outcasts,” for instance. The book shows how thorny that whole notion is. Some of the characters can, to varying degrees, opt in or out of being an outsider, while others don’t have a lot of choice. They’ve been alienated, and they’re likely to stay that way. That’s one tiny slice of what makes the book fascinating—cutting deep into how our identities are shaped. For me, the book is also about the constraints of language, the necessity and risks bound up in empathy, the emotional fuel behind confirmation bias, and maybe most importantly: how a human need for understanding can make us see order and meaning that’s way too tidy or that simply isn’t there.

Getting back to the hypnotism thing—what I mean by that isn’t figurative. I almost always read novels in one sitting, and when I did that with String Follow, there was a point where I think the narrator actually hypnotized me and then flipped things around and made me aware of it. The book’s voice is intense, and there were times I felt like I, specifically, was being told this story (which is also part of what the story is about—it’s layers on layers on layers).

The best part, though, is String Follow does all of this without ever lapsing into a philosophical treatise that pounds the reader over the head. At its heart, it’s always a story that’s hilarious, horrifying, and deeply tragic.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fifteen minutes later, Chris sent the following addendum

Here’s one of the Benadryl-driven outtakes (I think) I wrote. Maybe this is more what you had in mind?

All right, so, roughly thirty years ago, someone I’d known for only a day or two gave me a mixtape. I took the tape home and listened. I don’t remember anything about the songs. I remember there were only three of them, which I thought was weird—the rest of the tape was blank—and I remember very viscerally not liking those three songs. The next day, the person who made the tape called and asked, “Did you listen to it?” I said I had listened to it, yes, and then I went through the silent turmoil of trying to think of something grateful to say while not encouraging more mixtapes but also avoiding hurt feelings (music is such a personal thing and making a mixtape is a weirdly intimate gesture, even when the tape has only three songs).

Before I could say anything, this person I’d known for somewhere between twenty-four and thirty-six hours said expectantly: “Did you have strange dreams?”

Sirens and flashing lights went off in my head. I politely got off the phone and threw away the tape. But thirty years later, I navigate the world in a persistent state of anxiety: What were those three songs? Were they lyrically connected in some way? Did their combination symbolize something? Was the rest of the tape really blank? Intentionally? Could what sounded like blankness really have been encoded with subliminal messages?

String Follow completely freaked me out in the same exact way. It felt like hearing what might have been on the rest of that tape, embedded in the silence.

APRIL 25, 2022: Borne by Jeff VanderMeer

Post by Sean McDonald, Publisher of MCD

Five years ago today, we published Jeff VanderMeer’s Borne, the very first book on the MCD list. We were coming off the publication of the Southern Reach Trilogy, which had been a huge success for us on the FSG Originals list, but it was still before Annihilation had become the strangest movie to ever star two Star Wars stars. And Borne pioneered so much of what would become hallmarks of MCD: gleefully blending genre and literary ambition; an obsessive interest in themes of ecology and identity; mind-blowing design by Rodrigo Corral & team (Borne Illustrator Tyler Comrie has just returned for the paperback covers of Hummingbird Salamander and the Ambergris trilogy); a determination to push the boundaries of format and storytelling (the Borne universe would expand to include–in ebook, paperback, and hardcover originals–both The Strange Bird and Dead Astronauts); and, we hope, an abiding sense of generosity and community that would help the whole MCD list feel like an organic whole.

But five years ago, we were just trying to bring to the world a brilliant, beautiful novel about a little green shape-shifting lump of life, neither plant nor animal but exuding undeniable charisma…which at the very least gave some indication of how rational and normal this whole enterprise would be. For the next few months, we’ll be sharing our highlights from the last five years and, of course (mostly), trying to prime you for five more. Five years of MCD, and we’re just getting started.